23 photos

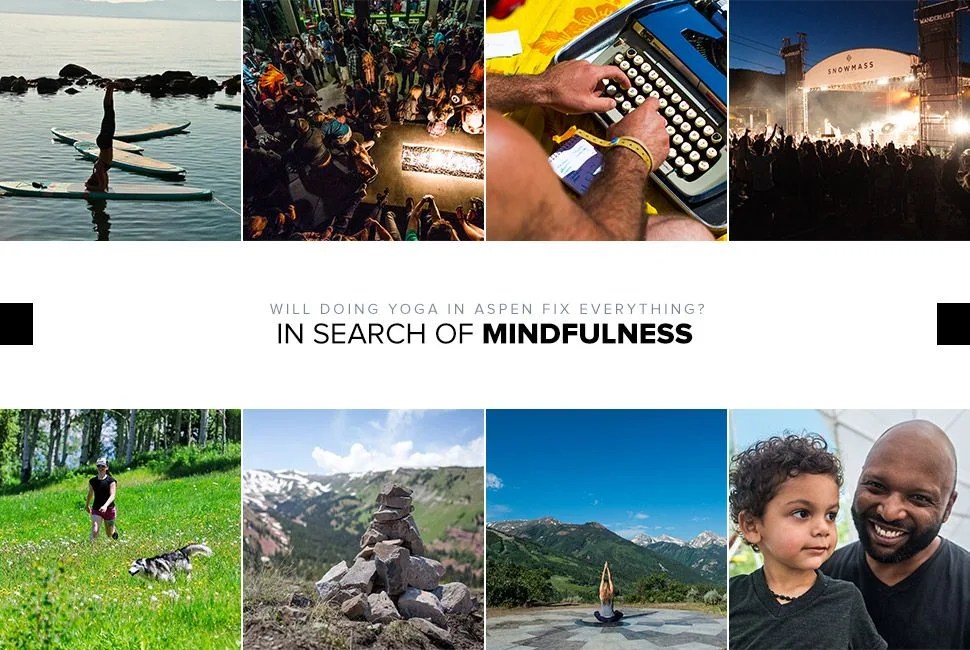

I was out of my wheelhouse. Far out. Specifically, I was at the Wanderlust Yoga Festival: a touring, four-day celebration of all things mindful, beautiful and spiritually well-aligned that had settled this weekend at the slope-side village of Snowmass, Colorado. Festival organizers had transformed the village into a sort of crunchy paradise – vendors hawked clothes, granola, and healing crystals from brightly colored tents, and speakers piped out a rhythmic but nonthreatening variety of hip-hop.

MORE MIND-BODY EXPLORATIONS Vermont 50 Ultramarathon | Learning to Freedive | Three Weeks in Cuba: Photos and Stories

My fellow attendees were fit, flexible, and overwhelmingly female. They were wealthy and lithe – the sort of people who can afford to shell out $525 for four days of spiritual communion (and God only knows how much for lodging). Even the men radiated the sort of soft glow that comes along with fastidious skin care and a diet rich in leafy greens. They were beautiful.

I was — and remain — a yoga novice, a 200-pound bald man with a blotchy face and a borrowed yoga mat clutched to my chest like an emergency flotation device. This wasn’t my scene. But I had a press pass. And an assignment. And, like any self-respecting journalist, I had some questions.

Like: how the hell did this all get here? How did a pre-Vedic Indian spiritual practice become the big-ticket attraction in Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley? What was the connection between enlightenment and butt-lifting compression pants? What, if anything, could this movement teach a slob like me?

And make no mistake, it is a movement. More than 20 million people in the U.S. practice yoga, and spending estimates on yoga classes, equipment, and apparel range from $10 to $27 billion. (To put that in perspective, the NFL brought in just $9.5 billion in revenue in 2012.) The practice has steadily gained traction in the U.S. since the 1980s, and it shows no immediate signs of stopping. Practitioners and (some) medical researches alike describe yoga as a panacea of sorts, offering a cure for everything from hypertension to joint pain to ennui.