In the years following World War II, motorcycles were incredibly unpopular, aside from police officers and servicemen who rode them their work. Before 1960, less than 600,000 motorcycles were registered in the United States. At the time, the majority of bikes sold in the US were Harley-Davidsons and Indians: slow, heavy and dangerous cruisers that quickly became (somewhat erroneously) associated with biker gangs and rebellious youth. There also was the British sports bike, including motorcycles from Triumph, Vincent, BSA and Norton. These bikes were lighter and faster, and could handle a twisty road. But, owning one was not for the faint of heart — they were incredibly finicky and too expensive for the average rider.

Come 1959, Honda began to establish itself as a contender in the United States motorcycle market with its US subsidiary, the American Honda Motor Company. In an effort to dispel the stigma of the motorcycle being for the rowdy and dangerous, Honda launched its infamous “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” campaign. Rather than targeting preexisting motorcycle buyers, Honda aimed for those who hadn’t considered two-wheeled transportation before. The plan worked. By 1965, motorcycle registration in the US increased to nearly 1.4 million motorcycles. By 1966, Honda had over 60 percent of the American motorcycle market.

At that time, Honda’s offerings were small. Central to the “You Meet the Nicest People” campaign was the Honda 50 (known in non-US markets as the Super Cub), and the biggest motorcycle Honda made in the mid-’60s was the CB450 “Black Bomber” — a fantastic middleweight, but lacking for riders who wanted more performance. Hondas made for great starter bikes, but, as Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) chairman Edward Turner noted in 1965, people quickly wanted to graduate to large bikes, which were only supplied by the British brands. Rather than give up future sales to the Brits, executives at American Honda implored their parent company to develop a bigger, better Honda.

“In the hard world of commerce, achievers get imitated and the imitators get imitated. There is developing, after all, a kind of Universal Japanese Motorcycle…conceived in sameness, executed with precision, and produced by the thousands.”

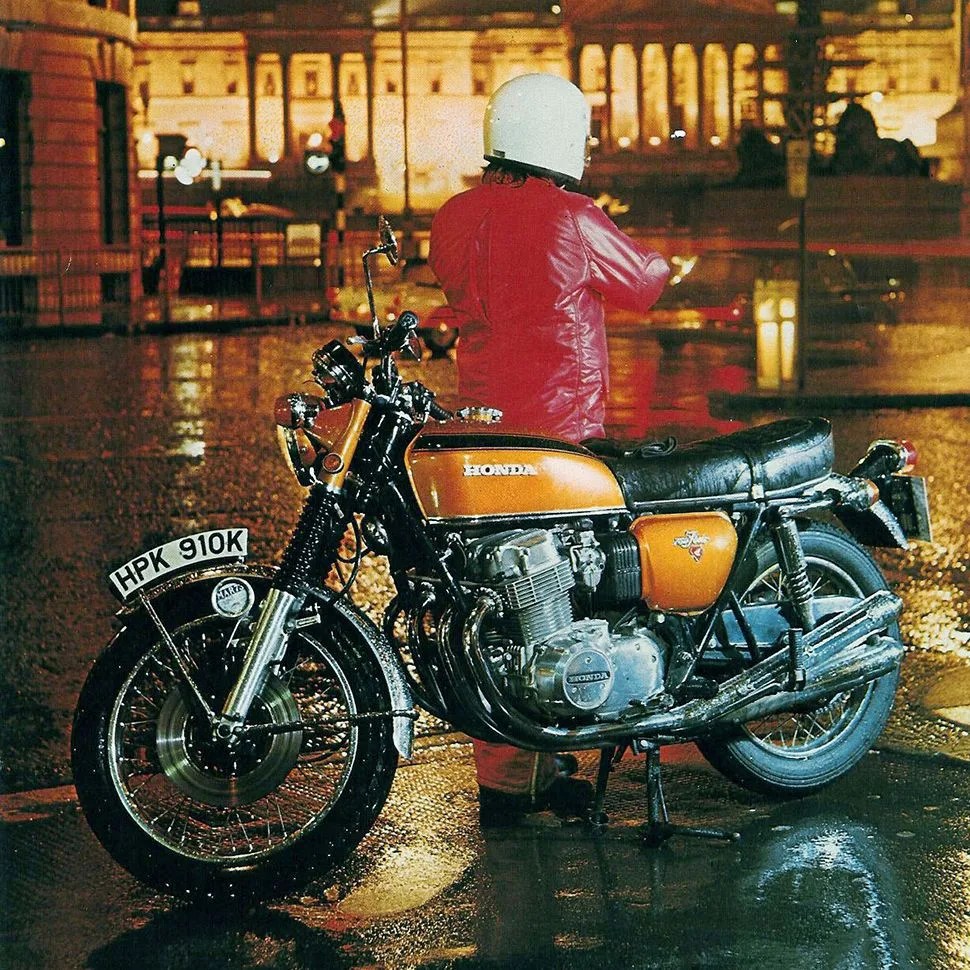

The result: the Honda CB750. First unveiled in October of 1968 at the Tokyo Motor Show, the CB750 shocked the world. The power plant of choice was a Grand Prix-derived SOHC inline-four engine, and stopping power came by way of a disc brake on the front wheel. The CB750 also utilized an electric start and a five-speed gearbox. Though these features weren’t entirely unheard of for a motorcycle at the time, never before had they been combined together on an attainable, mass-production motorcycle.

The CB750 immediately became a performance benchmark and made its rival of the time, the BSA Rocket 3, look instantly antiquated. Its 736cc engine made 67 horsepower (the BSA made 58) and could propel the bike and its rider to over 120 mph. What’s more, it was reliable. It didn’t have the tendency to leak oil like the British bikes and the electric start made it far more user-friendly. And with a starting price of $1,495 (about $9,689 today), it seriously undercut prices for similar bikes from British manufacturers.

When Honda revealed the CB750, Kawasaki was well into its own project for a 750cc four-cylinder bike. But since Honda beat them to market, Kawasaki scrapped the bike and went back to the drawing board in order to one-up Honda. So began the “New York Steak” project, which in 1972 yielded Kawasaki’s newest heavyweight, the 903cc, 81 horsepower Z1. More powerful, faster and more aggressive than the CB750, it became the new benchmark, although the Z1 and CB750 weren’t all that different. Both had powerful (for the time) four-cylinder engines, electric starts, disc brakes and upright riding positions; both bikes offered more power and more reliability for considerably less money than their European counterparts; but the Z1 pushed the limit a bit farther.