The MotoGP world is a moving army. In Europe it moves by semi; abroad, it moves by plane. Teams pack things into gigantic modular flight cases — including all the tools and bikes and computers — and then Dorna, the race organizer, ships the cases on a big cargo plane, which is rumored to be Russian made. The mechanics show up to the track on Wednesday and set up the garage. Thursday, riders arrive and there is a press conference at noon. Friday is preliminary laps. Saturday, qualifying. Sunday, race. Monday, pack and ship. Tuesday, travel. Wednesday, repeat. The army marches on.

At times, there are larger gaps between races; at times, the gap between races can be as short as a week. The schedule is quick, the races fast, the teams close, and the entire production massive. The racing season is this: December to January, a testing ban with no riding, when teams tinker with bikes and computers and technology, all independent of the track. February to March, two testing events in Malaysia. Then, actual racing starts in April, in Qatar. The season runs to November, where it culminates in Valencia, Spain. Outside of the races, teams don’t work on the bikes — they can’t go into the shop and riders won’t see track time (with the exception of pre-set, regulated practice sessions in the race calendar). When the race is on, it’s on, full throttle, maximizing bike and rider performance as much as possible in a short amount of time.

I’m here in Austin at the Circuit of the Americas with a handful of credentials provided by Honda, whose motorcycle racing arm, Honda Racing Corporation (HRC), covers five sports: MotoGP, MotocrossGP, Rally, Trial and AMA Supercross and Motorcross. This weekend, two motorcycle events overlap — the MotoGP in Austin and the AMA Supercross in Houston. Honda, the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer, wants to win them both. But what matters most — the racing at the highest possible level on the most competitive stage — is the MotoGP.

10 photos

Media Day

Thursday, April 9, 2015 | Austin, TX

Day one, Thursday, is a media day, so no bikes on the track. This is interview time, time for engineers to work on the bikes in the garages. I sit down in a group interview with Honda Racing Corporation’s Technical Director, Takeo Yokoyama, who has a mullet and seems like a genuinely cool guy. He used to play baseball — he was a pitcher — and wanted to turn pro, but he found out he wasn’t going to make it. So, with a change of life plans he worked his way up through the ranks and now he’s Honda’s main man. He comes across as intentional and takes questions seriously. He wears a watch with four dials and a Polo shirt. Everything is branded. When asked what the team does to relax after a race, he says, “We party.” The guy next to him is Livio Suppo, the Team Principal for Repsol Honda. He used to be with Ducati. He has a salt-and-pepper beard and big lips and straight teeth and his breath smells like cigarettes. All these guys smoke.

One old reporter is talking about chassis in highly technical terms. I ask more basic questions. Suppo starts out completely disinterested in conversation, checking his stocks under the table, but then he warms up. He starts telling stories, and by the end of the interview he seems to be genuinely enjoying himself: “You remember when Ducati put those two pieces on the chassis? The ones that stuck out to here?” He’s an entertainer at heart. He seems like someone who can’t avoid his own impulses, like once he’s started rolling on something he’s just going to roll.

The interview is it for the day, and it’s uneventful. What’s been established is that the team is here to work, not to pander to media. After 15 minutes of interview, Suppo and Yokoyama are swept away.

Free Practice Day

Friday, April 10, 2015 | Austin, TX

Free practice is made up of two one-hour sessions, during which riders get reacquainted with their bikes and the track at 90 to 95 percent full throttle and teams work on getting everything tuned up before qualifying. This is the first time in two weeks that riders have been on their bikes. It seems both difficult (for the athletes) and slightly unintuitive (for the teams) to allow such downtime without practice, but it works within the heavily regulated structure of MotoGP.

Though Dorna, the organizer and supreme regulating board of MotoGP, seems to be a little reviled among the teams, Honda benefits from a good working relationship with them. As the largest manufacturer of motorcycles for the event, Honda is also MotoGP’s most “relevant” participant — something akin to the Yankees in MLB. It’s good to have Honda in MotoGP for many reasons: Honda brings a lot of fans, their athletes are competitive, and they consistently push bike technology forward, working to make bikes more efficient while maintaining power. The last point tends to work in Honda’s favor, especially in light of Dorna’s fuel regulations — a policy that Honda (along with other teams) helped develop.

Like tires (which are limited to 240 per season), fuel in MotoGP races is regulated. This is done in the spirit of improving the fuel consumption of the bikes, and falls in line with the widespread motoring movement toward more efficient engines. During races — which run without pit stops — bikes are limited to 20 liters. The regulation is beneficial to Honda, who has developed the most efficient and powerful engines to date. The advancement of the sport, and improvements in efficiency in engines, is, of course, a good thing, and as Honda pushes the technology further into a more efficient and powerful future, all benefit; for now, Honda benefits the most. Some teams, like Ducati, are allowed exceptions, as their bikes are not quite performing at the level of efficiency and power of other manufacturers. To keep them competitive and in the spirit of good sportsmanship, they’re allowed more fuel. At Qatar, Ducati was allowed to have 24 liters, and they had 2 bikes on the podium. This weekend, they are allowed 22 liters.

The bikes rip around the track, which today is wet from rain. There’s a high whine from their engines, though it’s less abrasive than the scream of an IndyCar or Formula 1 race car (or, even more loud, Formula 2). It’s a sound the mind immediately associates with extremely high speeds. After the practice — which today was notable for the rain and a dog running on the track — the teams usually “scrum”, or give a short rundown to the media of how things are progressing. Today, due to the rain and the dog, the scrums are canceled. Instead of facing a media blitz, Marc Marquez, the reigning champion and Repsol Honda’s number-one rider, pops out of the team garage wearing his racing leathers, signs a few autographs and walks briskly to his personal trailer. His celebrity is obvious on the faces of those who watch where he walked.

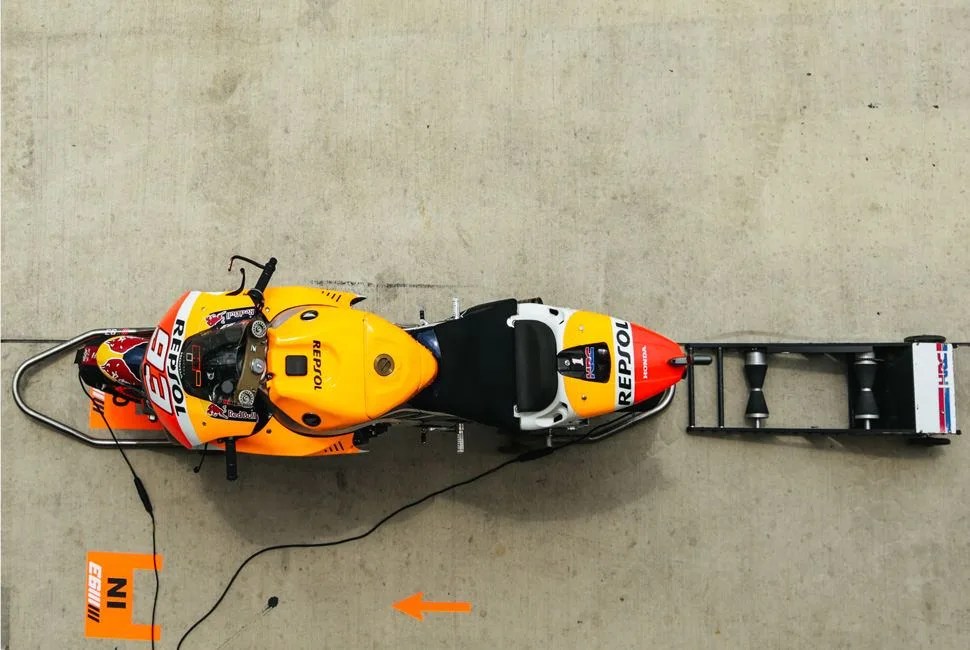

Once the practice is complete, the bikes are disassembled, cleaned, and then put back together. All the guys — mechanics, engineers, riders — look compact and tightly wound, a little like carnies, but with better teeth and more purpose. Rock music prevails around the paddock area, chosen by the mechanics, one assumes. Hoses and air compressors are everywhere, cleaning parts.

24 photos

As the day progresses, the scattered showers clear and things warm up. During Free Practice 2, teams switch from rain tires to slicks. I ride a shuttle out on the 3.41-mile track to take photographs of the riders entering Turn 11, where the bikes come by, quite literally, an arm’s reach away. The volunteer who shuttles me to the spot in the track, an old hand at races, glances at the grassy infield covered with flowers as he drops me off. “I love the GP of the Americas because the blue bonnets are always in bloom,” he says.

At events like these there’s the wonderful sensation that if you just have the right number of credential cards hanging around your neck — I have five, and a wristband — you can go and do whatever you want. And essentially, you can. After Free Practice 2 concludes, Marquez stops to chat with media, briefly, outside the paddock. As Marquez is being interviewed there’s a large man with black glasses and curly hair who looks and acts like a bouncer standing close by. He makes small hand motions to another guy on the other side of Marquez. He’s intimidating. I approach to hear Marquez better. The bouncer looks at me. “You media?” he asks. I flash a random badge. He relaxes.

Marquez is small and has the good skin and polished look of a classic Spaniard. His one visible imperfection is a scar on his right wrist, most likely from arm pump surgery (technically, chronic exertional compartment syndrome [CECS]), something that nearly all motorcycle racers deal with at some point in their riding careers. It is triggered by excessive blood flow to the arms, brought on by the positioning of riding a motorcycle and the extreme strength it takes to wrangle these bikes around a track. Dani Pedrosa, the number-two rider for Repsol Honda, recently had his third bout of this operation — which essentially cuts a slit in the fascia (the sheath surrounding a vein) so that blood can flow more unrestrictedly to the extremities. Pedrosa is missing two races from the operation. In Austin, Hiroshi Aoyama is taking Pedrosa’s place.

Marquez is patient as people ask questions like, “What’s worse, racing in the rain or with a dog on the track?” or, “Are you hoping to win on Sunday?”

“Of course, of course,” Marquez responds. “It is the target. Try to fight for the victory on Sunday, and try to get it. But you never know. But the target is this. We try to work for victory.” He is easy to like. I am immediately on his team.

AMA Supercross

Saturday, Apr. 11, 2015 | Houston, TX

Saturday, in Austin, the MotoGP has qualifying. Marc Marquez will take pole position in one of the most memorable laps in MotoGP’s short history at Circuit of the Americas. The Spaniard will have bike trouble, and will then come into the pits, swap bikes, ride out and have one last shot at putting together a qualifying time. He will throw the bike around the track, coming into corners hard on the brakes and up on the front wheel, accelerating out on just the rear wheel. He will get the fastest time. It is one of the highlights and most talked-about moments of the weekend. I, though, will miss it, as I am en route to Houston, where the one-day spectacle of the Monster Energy AMA Supercross is happening at the NRG Stadium.

Supercross — motorbike racing on dirt, in stadiums (mostly indoor), with jumps — starts in January. As it’s early April, we’re late in the season. Races take place every Saturday (except one rest week), in an all-day program. Supercross runs in the winter, and its counterpart, Motocross — which involves the same teams and riders, competes outside on longer tracks, is hot, spread out and less spectator friendly — runs in the summer. Supercross, with the jumps and the fireworks and the Monster girls, is much more of a spectacle. To the unacquainted, it may come as a surprise that Supercross is owned by Ringling Brothers Circus. To those that have been to a race/show, it makes perfect sense.

The day lays out like this: at 10:30 a.m., both classes of riders (250cc and 450cc) walk the track, seeing the layout for the first time. Then, there’s open practice. Then three qualifying sessions. And then the main program starts at 6:30 p.m. All is over by 10:30 p.m.

Motocross, which predates Supercross, was born out of scrambles, which started in England in the early 1900s (most cite 1924 as the first scramble). Though the races were popular, things didn’t fully take off until after WWII, when riders in both England and America began pushing their bikes as hard as they could with the suspension travel available to them. Then, in 1974, more suspension was added to bikes, which marked a huge development in the sport, as it allowed greater clearance, which let riders take on more varied terrain at faster speeds. Supercross started mid-’70s with the additional suspension, and over the past 40 years it has gained traction primarily in the United States.

29 photos

Some say that the technology in Supercross racing has gone too far. The bikes have become faster and the jumps bigger, and therefore the racing has become more dangerous. Fifteen-year-old racers are hitting 120-foot jumps, without the ability to both understand and properly prepare for the inherent risks within. A few years back, a young kid crashed on a jump and died of brain injuries on the spot. Less lethal injuries occur all the time. There’s a saying in motorcycle racing that it’s not the speed that kills you, it’s the sudden stop. In MotoGP, riders usually can slide to a gradual stop out on the shoulders of the track. Serious injuries and deaths typically only occur if a MotoGP a rider is hit by another motorcycle. But in Supercross, riders are coming back to earth abruptly and fast. There’s the landing to deal with, and then there’s getting landed on to deal with. Riders are essentially wearing beefed-up polyester and a chest protector and knee braces, and for the most part the gear they choose to wear doesn’t protect from serious injuries. They’re required to wear a helmet and high-end boots, but chest protectors and neck braces are optional, not mandatory. Neither are adequate for preventing injuries. One of the reporters with me, who is a former rider, says that because of concussions, he basically didn’t remember the summer of 2008. Travis Pastrana is, it’s discussed, a few brain injuries away from totally going kaput.

In the stadium, there’s a distinct smell of high-performance fuel. It is unusually pungent — and the first thought on entering is that there’s something wrong with the ventilation. The high whine of engines echoes through the big dome; between the fuel and the noise and the bikes flying through the air and the fire and the girls the whole thing feels fittingly circus-like. This entertainment-oriented setup has registered with the American crowd. Supercross is significantly more popular in the US than MotoGP, despite MotoGP being more popular with the global audience.

For today’s race, Honda’s top rider, Trey Canard, is hurt. (He was injured in Detroit when he landed on another rider during qualifying.) Honda’s rookie, Cole Seely, is the hopeful here in Houston. Seely is 25 but looks 16. He’s calm and quiet, and before the race, hanging out in the paddock area across the street from the stadium, he seems nearly unaware that he’s about to ricochet through a dirt course made to filter the best riders in the world out from their lesser brethren. Things are casual. He signs autographs. Does an interview.

Then he excuses himself into the trailer and we head back to the stadium, awaiting the start of the show. Flames burst forth into the stadium sky, and an announcer starts the spectacle. In the 450cc race, Seely lands the holeshot and spends the rest of the race extending his lead. Out front, he looks casual and composed, kind of dancing the bike through the course. He’s a fluid and beautiful rider, and without the stress of passing, he’s able to pilot his bike elegantly to an enormous lead. As the checked flag rises, Seely launches through an overhang that sends flames into the air. He wins.

The Grand Prix

Sunday, April 12, 2015 | Austin, TX

On Sunday, I drive back to Austin to watch the final day of the MotoGP. The weather shows no signs of rain, and the track stays dry. With the sun out, everything becomes more vibrant — fans turn out and the grandstands, about half full, are lively. Models under umbrellas walk the paddock area before heading to the starting line. An announcer calls out the days’ events on a PA. VIPs mill about in the paddock and the VIP seats. Overall, it’s a lot of stimulation: Hot bikes, fast speeds, hot girls, free drinks, hot weather, high security (in trying to access the starting area, my tags get rejected for the first time). The women in the VIP section wear stylish outfits, from jumpers to plaid shirts to Daisy Dukes to leather. Valentino Rossi (as of publication, the MotoGP points leader) is the most popular MotoGP racer. His nickname is “The Doctor”, and there are many who wear his shirts. “He’s basically a brand,” I’m told.

The millions of dollars that the teams put into the bikes, the lifetimes of R&D that go into the construction and tuning, the perfectly cleaned and pneumatically dried parts — they all lie under the control of the small, jockey-like man on the bike.

It’s all a bit ridiculous in the way that fans of sports can be ridiculous, but, through it all — and with access to the paddock area, the spectacle spreads everywhere — the people who stay unbelievably focused are the engineers and mechanics. I am shuffled through the Repsol Honda garage, and inside the garage, life seems quasi-boring. This is engineer land, where a tweak to the software is more striking than the bikini-topped Red Bull girl who walks by outside. These are just a bunch of nerds, getting million-dollar bikes into ridiculously precise shape. And for now, most of their work is done. The bike is ready for the race, happen what will.

This is the point where MotoGP becomes spectator friendly and not just engineer dorky — this is where the element of the unexpected is introduced most robustly. You see it with the rain, you see it when a dog runs on the track. Weird things happen in Free Practice and Qualifying, sure, and people have to improvise and make due. But when the race comes, it’s go or nothing. As all the racers line up and set off around the track, the millions of dollars that the teams put into the bikes, the lifetimes of R&D that go into the construction and tuning, the custom-machined components, the perfectly cleaned and pneumatically dried parts — they all lie under the control of the small, jockey-like man on the bike and the men and elements around him. Anything can happen in 21 laps.

29 photos

Marquez starts in pole position, but as the race starts, he lands in second. A couple laps in, he passes to take the lead. In Honda’s VIP viewing area, the race is broadcast on flat-screen televisions, along with rider stats. A small cheer echoes through the room. Outside, in the grandstands, the riders fly by on the final straightaway. At the race’s start, people cheered, but by mid-race, there’s a certain studious nature to viewing. The half of the fans there for the racing, and not the see-and-be-seen nature of an international racing event, keep focused on the battle for second place, where Rossi and Andrea Dovizioso jockey for position. The others drink demurely. It’s early afternoon on a hot Sunday.

But for however little attention is being paid to the race as a whole, every time time the bikes come down the straightaway, people’s heads turn. Marquez, like Seely the day before, quietly extends a lead, piloting the bike around the track with balletic grace.

The finish is unsurprising. Marquez extends his lead and wins. He is ridiculously fast. His bike is ridiculously fast. At the race’s finish, the merrymaking — with Takeo Yokoyama and his crew — seems a bit excessive. They all leap on top of each other, jumping up and down, a sort of pitching mound celebration down in the pits. Because of the process- and data-driven nature of everything leading up to this point, it comes as a bit of a surprise. But, it is justified. This is the ultimate level of racing with the ultimate motorcycles on the ultimate stage. This is as quick as two wheels go. And there’s an entire army that works to plan those 40-odd minutes it takes for the rider to complete the laps. Their collective effort produced a result better and faster than everyone else and for this race, this weekend, that’s reason to celebrate.