From Issue Seven of Gear Patrol Magazine.

Imagine if Jaguar unveiled the E-Type this year. But not a bloated, modernized version of the classically beautiful 1960s automotive icon, akin to the rebirth of the Dodge Challenger, say, or the Ford Mustang. Those vehicles just vaguely echo the shape and spirit of their predecessors but possess nothing that remotely approaches their actual visual or visceral experience.

No, picture Jaguar literally coughing up the original E-Type on the podium in Geneva, with its wistful lines, diminutive presence and soul-enriching ride. Sure, it would have a modern suspension, finely tuned carbon brakes and an efficient engine that will turn over instantly 30,000 times in a row — but generally the same car.

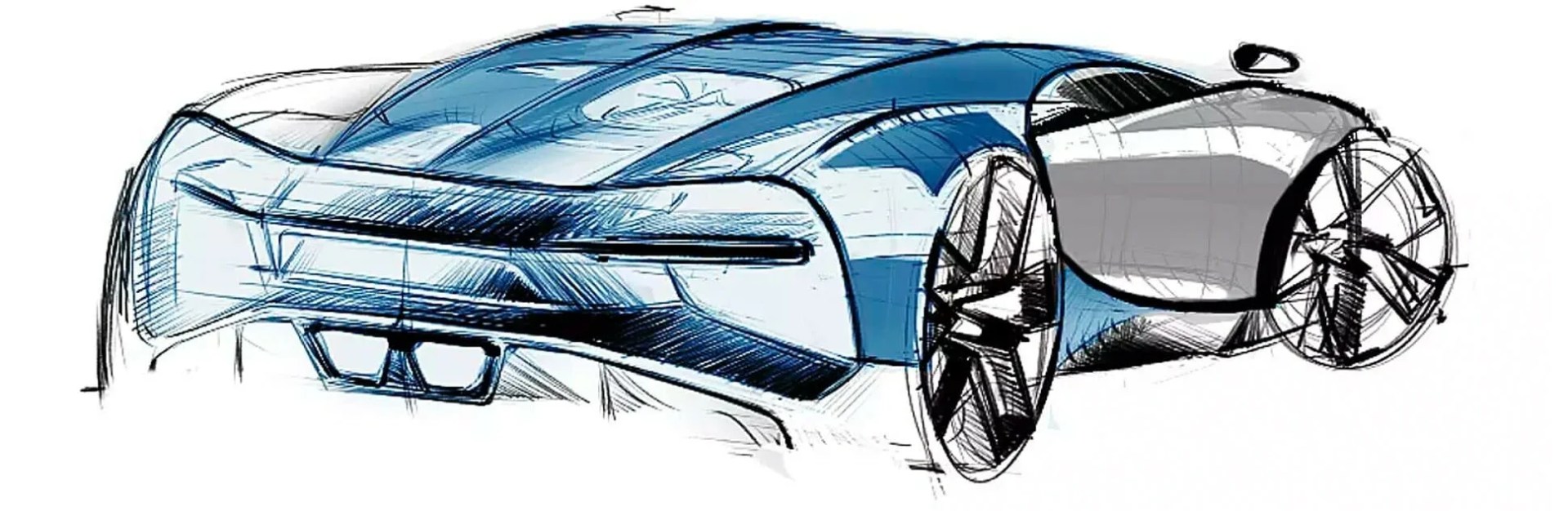

Could they build it? Could they generate something so simple, elegant and purposeful, a vehicle that seems to have bent the world to its will? Chances are no — but the reasons are more complex than you might think.

First and foremost, you have the U.S. government. Beginning in the 1950s and then accelerating in the ’70s, government regulations have forced carmakers (necessarily, thankfully) to make their vehicles safer and more efficient. They’ve achieved this via thousands of rules and regulations mandating everything from bumpers to airbags to anti-lock brakes to levers you can pull to pop yourself out of a trunk and regulating such minutiae as headlight placement and the field-of-view in rearview mirrors. The regulations also go into great detail about crash-worthiness, requiring manufacturers to design steering wheels that won’t impale drivers during a front-end collision and glass that won’t turn into sharp flying daggers when punctured, among many dozens of other rules.

This alone has changed vehicle design drastically, to some extent homogenizing it by stipulating various minimums and maximums, but also dulling it thanks to prohibitions against, for instance, shiny chrome bumpers that can slice and dice pedestrians in a collision. Over the years, we’ve thus been left with vehicles that have grown larger, heavier and more complex, with fewer and fewer possibilities for truly creative design work. So producing a Jaguar E-Type, or something like it, in the same approximate packaging as the original would require herculean engineering prowess.

Such purity of design is also frequently stymied today by the many masters of modern vehicle production, which go far beyond even the government’s regulatory requirements. Designers must answer to the practical needs demanded by a given vehicle’s category — comfort, visibility, storage and other factors. They must also yield to — or at least do battle with — the accountants over the cost of their grand visions, the customers whose whims can make or break even the most brilliant and bold visions and the engineers who ultimately determine the manufacturing feasibility of a given component or entire design.