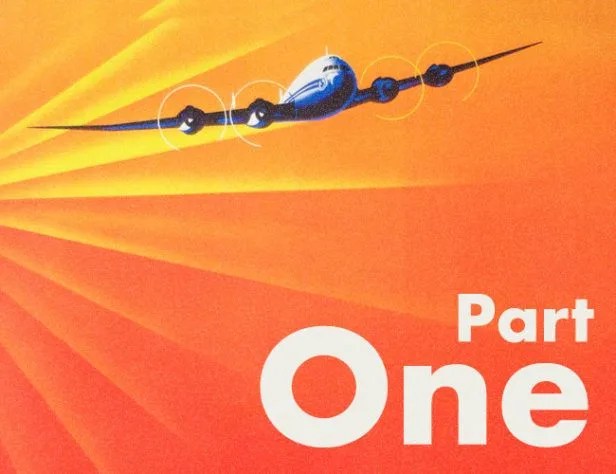

Editor’s Note: This post is the final part of a three-part series about learning to fly by Mike Arnot, founder of men’s design brand Boarding Pass NYC (formally Owen & Fred), a writer and now a licensed pilot. We’re excited to share Mike’s story, and hope you might become inspired if you’ve ever wanted to take to the skies. Take a look here for all three installments of Mike’s story.

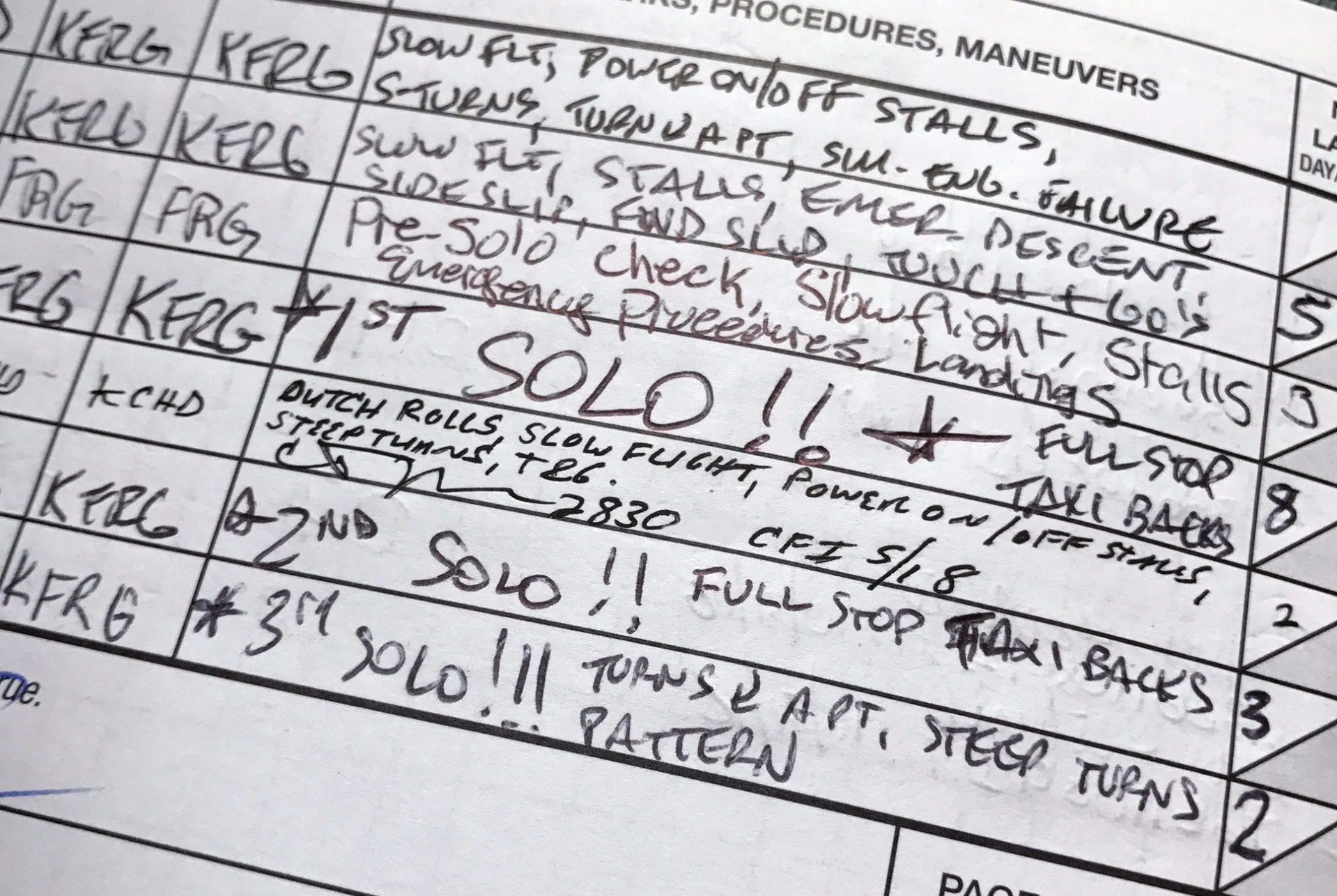

It was a beautiful, crisp late fall day on Long Island. I awoke at the ungodly hour of 5:30 a.m., had a shot of espresso and drove out to Republic Airport. The plan was to get started early so that I could beat any traffic on the ground — and any traffic in the air.

Republic is a historic airfield. Several thousand aircraft were built here from the late 1920s through the 1980s by major names in aircraft manufacturing such as Fairchild, Grumman and Republic Aviation. Some 9,000 P-47 Thunderbolts alone were built at Republic for the war effort. To this day, Republic bustles with activity, as it is a major student training hub and a commercial aviation center for the jet set (or for old folks heading to Atlantic City for the day).

This day, December 13, 2016, was going to be the day I soloed — the day I would fly an aircraft alone for the first time. Soloing is a rite of passage after many, many hours of rigorous preparation. On the day I soloed, there was very little wind, a fact I surmised from seeing smokestacks and heat vents around the airport blowing straight up.

My aircraft was a Cessna Skyhawk 172SP, with an 180 horsepower Lycoming engine. Its tail number was N6185U: “Six One Eight Five Uniform” in the NATO phonetic alphabet used in aviation circles. It was the first plane I had taken a discovery flight in the previous summer.

Just after sunrise, I met my instructor, Greg, who had been in my shoes a few short years ago. He always wanted to be a pilot; now, he’s training others along the way to flying the big jets. We did the normal pre-flight preparations that are required, taxied out to the runway, and took off to practice some touch-and-goes. All went well, and Greg asked me to bring him back to the plane “parking lot” and drop him off. It was my turn to solo. I shut off the engine and Greg got out; he shook my hand, he took a photo of me at the controls. He didn’t wish me good luck. It was an unspoken understanding that I was ready for the privilege, had earned it, and that luck had nothing to do with it.

Then Greg walked away, and I was at the controls with no instructor for the first time.

In truth, you’re never alone. In the time between your first flight and your solo, you’ve absorbed new motor skills from months of training, representing decades of aviation know-how. You’ve got an instructor — a Greg — on the ground watching you. He or she puts their career on the line by allowing you to solo, so it doesn’t happen if you’re not ready. Then there’s the ground control, and separately the tower, who spy your movements.

Like every solo pilot before me, I let the tower know that I was a student pilot on a solo. You know they’re watching dutifully from above as you taxi to the runway. You get the feeling they’re really rooting for you, because they slow the pace of their radio communications a touch. The weather is always checked before taxi, and to verify that you have checked it, ground control issues you a secret phonetic alphabet code. In my case, the code was issued was “Mike,” which, given that it’s my first name, I took as a good sign.

I lined up in the middle of the runway and advanced the throttle to full power. The RPMs build quickly, and so does the speed. Fifty miles per hour never felt so fast. Using my feet to steer the nosewheel (and not the yoke, as you would in a car), I kept the plane pointed down the centerline until the airspeed reached fifty-six knots (roughly sixty-four miles per hour). With a gentle pull to increase the angle at which the oncoming air met the wings, I flew away from the ground.

The normal procedure for soloing is to fly around the airport in a circuit, land (should you be so skilled), and taxi back to take off again. You do this three times consecutively, and the experience is over. You’ve soloed.

“6185 Uniform, spacing for departing traffic, extend your downwind, I’ll call your base, you’re following a Challenger on one mile final,” the tower said.

I looked out to the left to see a Challenger private jet roaring past a mile away on its final leg inbound for landing. “6185 Uniform, extend downwind, you’ll call my base.” This means instead of being immediately cleared to land, I was required to fly a bit farther from the field. A little bit longer in the air. (Okay, fine, twist my arm, I thought.)

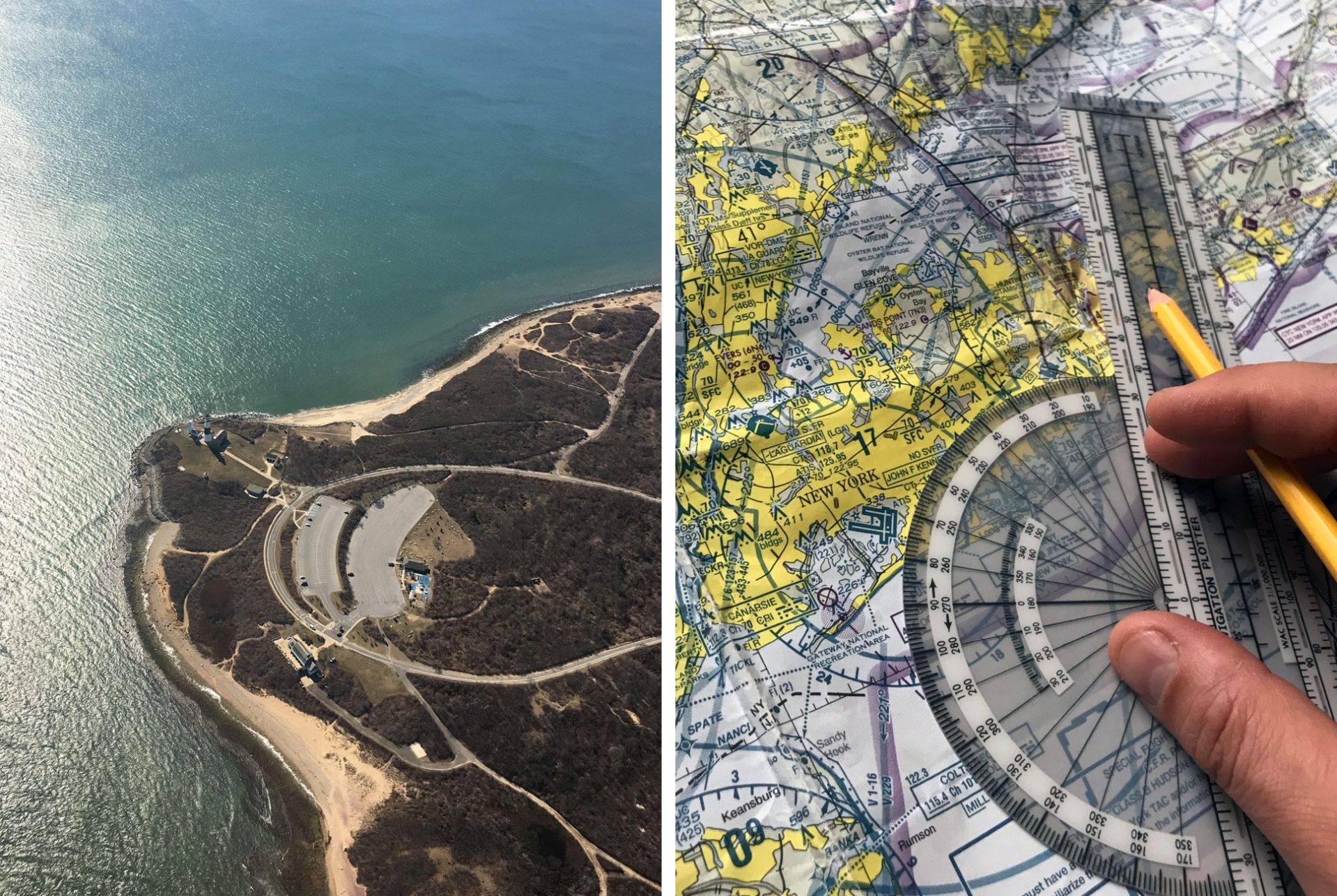

Quite focused on the task at hand, I could not take a photo to document it. But what I saw was gorgeous. The early morning shoreline of Long Island was glistening in the sun — a sun that was rising, red, and simply beautiful. It was cold out there, and the ocean ahead would be a frigid dip. Inside the cabin of the Cessna, it was calm, smooth and incredibly peaceful. I allowed myself to smile. There was no fear, and no real nervousness. I was focused on landing on the “numbers” — the twenty-nine-foot-high by nine-foot-wide numbers that mark the runway. On the ground, those numbers are the size of a one-bedroom apartment in New York City. When you’re in the air, they’re a speck. They get larger and larger as you descend to land.

After my third trip around, I was done. But I really didn’t want to be. The thought crossed my mind to keep flying circuits.

My logbook now reads: *FIRST SOLO!!*. It’s a moment that pilots say they remember forever. I know I will. I smile thinking about it. And that view.

Learning to Fly: the Three Part Series

It took decades of dreaming and days of training, but Mike Arnot is officially a pilot. Read the Stories