ROAD N✍TES

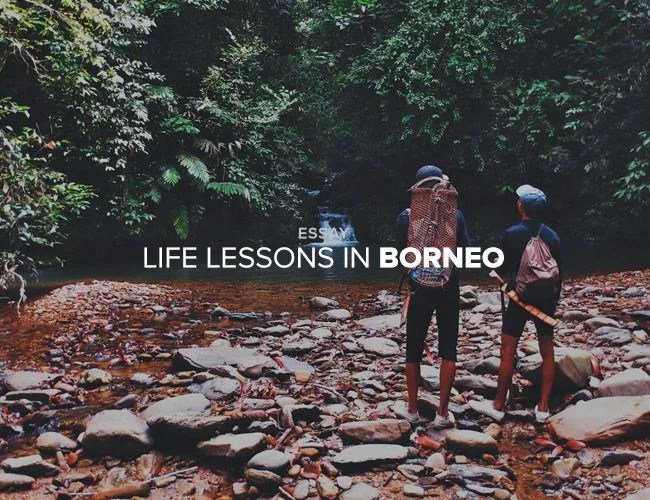

Editor’s Note: GP contributor Will McGough ventures into the thick jungles of Malaysia for a lesson in fishing, but reels in an unexpected lesson in humility as well. His essay below.

Deep in the jungle of Malaysian Borneo outside of Batang Ai National Park, about two hours from civilization, our guide uncoiled a weighted fishing net — which he had made by hand — and tossed it into the river. He put on a pair of old-school, glass-lens diver’s goggles and waded in, then dove down to retrieve the fish he had trapped and snapped their necks before tossing them to the shore. I collected the dead fish and put them into a bag. I was a complete bystander at this point, fully dependent on this man for my food. I decided that was all about to change.

It had been a long time coming. From the onset of the trip, my hand had been held. Our guides, Belansai and Udan, had led us an hour downstream in a boat, then carried all the food the hour hike to our camp, which they hand-built using a machete and trees from the rainforest. They guided us on hikes through the thick jungle to waterfalls, successfully tracked wild orangutans, fished, picked jungle herbs for seasoning, cooked, and showed us how to track boar and watch for pythons. Basically, up to this point, the only thing my friends and I had done was hand out nicknames. We called Belansai “the bamboozler” for his affinity for cooking in bamboo tubes over the fire. Udan earned the title of “Tuak” for his love of the Malaysian rice wine that goes by the same name.

In 30 seconds and one breath, I had broken the goggles — which Belansai used on a daily basis to provide for his family — and lost three fish.

On one hand, some pampering is expected on a guided trip. But as a self-proclaimed outdoorsman from Colorado, I wanted to be a part of it all, not perceived as some dipshit, worthless American. I saw the fishing as a reasonable opportunity to pitch in, so after Belansai had caught enough for dinner, I asked him via our translator if I could give it a go. He nodded and handed over his goggles. I stripped down to my underwear and, once in the water, put on the goggles. I went under, but water immediately poured into the mask.

WHEN IN BORNEO