On the day after Christmas, 2004, a 9+ magnitude undersea earthquake off the coast of Indonesia set off the deadliest tsunami in history. In the open ocean the tsunami waves traveled close to 500 mph, reaching the west coast within 16 minutes of the seabed’s rupture (just 5 minutes after NOAA Pacific Tsunami Warning Center issued tsunami warnings throughout the Pacific). The earthquake sent waves 30-100 feet high into the coast of Indonesia, as well as Sri Lanka, India and Thailand. With little warning and no way to outrun waves that reached miles inland, close to 225,000 people lost their lives in Indonesia alone.

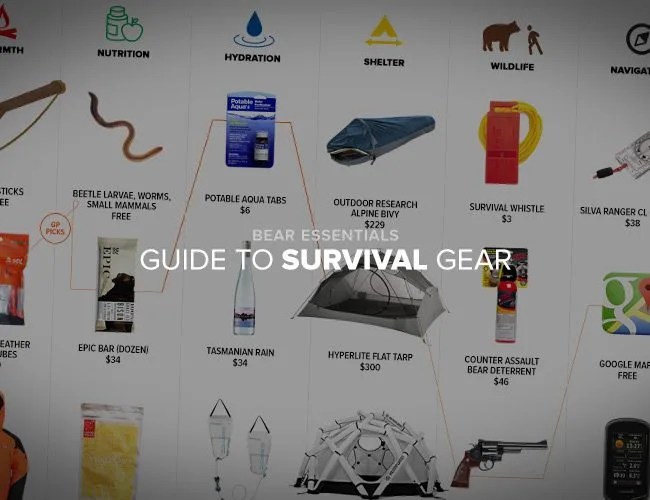

MORE ON SURVIVAL: Apocalypse Essentials | Guide to Survival Gear | Breakdown: Survival Kit

Six years later, on the other side of the world, an aerospace engineer named Julian Sharpe imagined a new solution: riding the tsunami. His idea was the Survival Capsule — a floatable and nearly indestructible sphere, with room for people and provisions. Just two months after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake caused a tsunami to crash into Japan, Sharpe submitted his Survival Capsule design to the 2011 NASA Tech Brief Innovation Contest. The design won ninth place and shortly went into production for testing.

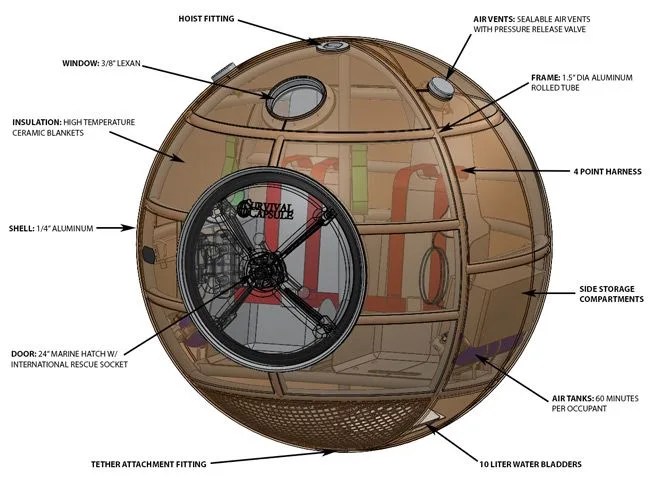

Not for the claustrophobic, Sharpe’s two-person spherical prototypes (capacity for some designs ranges up to ten people) are 4.5 feet in diameter, with a hatch, air vents and a small, submarine style window. An interior aluminum rib cage reinforces the pod to prevent crushing, insulation protects against debris fires and an exterior shell — in easy-to-find orange — shields from punctures and tsunami grade flooding. The capsules are designed to house provisions enough for 5 to 7 days, but, so occupants aren’t simply waiting and praying, the capsule comes with GPS, alert beacons, optional ground tethers and exterior hooks for rescue teams.

The capsules are designed to sit, stocked with provisions, in a backyard, garage or on a flat roof. After a tsunami alert is issued, residents in at-risk areas enter the Survival Capsule, buckle themselves into the seats’ four point harnesses and wait. The pod floats atop the tsunami waves (Sharpe compares the effect to trying to hold a beach ball underwater) and has an optional bottom tether to keep the pod from being swept miles away. The weight of the pod’s water storage tanks keeps the occupants upright and allows ventilation via air vents in the roof, and emergency air tanks provide 60 minutes of oxygen should the capsule become temporarily submerged.

While designing the capsule, Sharpe had his eyes on the Nankai Trough, a tectonic plate boundary that reports predict will be the epicenter of the next major event in Japan. The proximity of a potential Nankai earthquake to Japan’s densely populated coastal areas has lead to death toll estimates as high as 325,000, Sharpe told us. With this in mind, Sharpe hopes people will “change their view of mitigation, which is currently horizontal and vertical”; horizontally outrunning the tsunami is impossible if warnings come only minutes before the tsunami, and vertical evacuation towers have previously underestimated the size and destructive force of the tsunami events. Moving from the flatland coasts of Japan to the hills farther inland is impossible for some, including high risk groups such as the elderly or injured. These are who Sharpe hopes to help.