Underwater exploration has always been characterized by a struggle against nature. From early diving bells to rebreathers, the technology and design advances of man’s undersea endeavors draw an unsurprising parallel to the more popular exploration of space: they are the bizarre, sometimes insane systems of life support that defy nature, sending men where strong forces deem men should not be.

Marking the peak of this journey below sea level are underwater habitats, which have a 50-year history of scientific discoveries, tight living quarters, long decompression times (see sidebar) and insane amounts of risk. And just four habitats have advanced us from dipping our feet tentatively to emerging from a moon pool in a home away from home hundreds of feet at the bottom of the sea. Switch off The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and dog-ear Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. It’s time to study some subaquatic non-fiction.

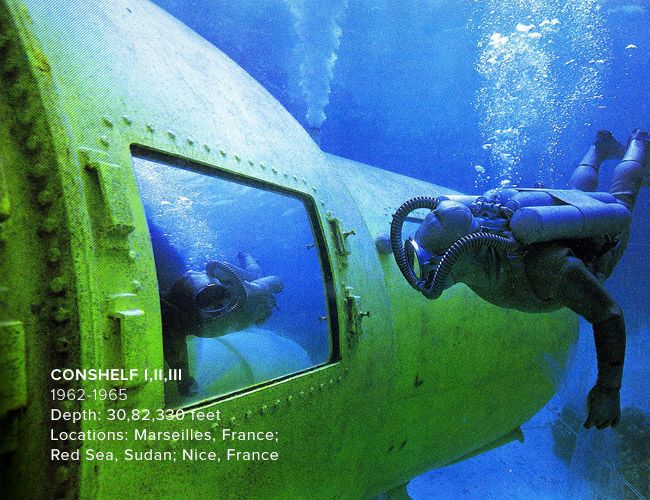

Conshelf

Created under direction from Jacques Cousteau, the Continental Shelf Station program (Conshelf) ran from 1962 to 1965 and was comprised of three separate habitats installed to research the physical and mental effects of sustained underwater habitation and saturation diving. A steel cylinder some 16 feet long and 8 feet in diameter, Conshelf I sat in 30 feet of water near Marseilles, France and was home to two aquanauts for seven days. During their stay, the Aquanauts were able to dive for long periods without the need for decompression time, allowing them to study wildlife and even establish an underwater farm. Outfitted with a radio, TV, library and sleeping quarters, Conshelf I was supported by a surface team of up to 30 people.

Conshelf I proved that prolonged underwater habitation was possible, leading to the 1963 launch of Conshelf II in the Red Sea of Sudan. With a larger starfish-shaped five-man main structure at 30 feet, a second structure placed at 82 feet and a two-man submarine, Conshelf II was a much more advanced installation. Cousteau directed a documentary about the Conshelf II project, called Le Monde Sans Soleil (World Without Sun), which won an Oscar in 1965 for best documentary feature. Some of the project’s funding came from the French oil industry, so Conshelf II’s aquanauts also performed experiments to study the practicality of industrial labor at depth.