11 photos

Surface intervals are usually necessary evils. Repetitive diving demands some decompression time on the boat between dives to allow body tissue to off-gas accumulated nitrogen. It’s like paying a debt for time borrowed underwater. These intervals are typically done bobbing in a small boat in the hot sun on nauseatingly rolling swells, eating overripe mango. The longer you stay topside, the longer you can spend underwater on your next dive, but you’re always impatient to get off the boat; the feel of cold water and weightlessness is a sweet reward.

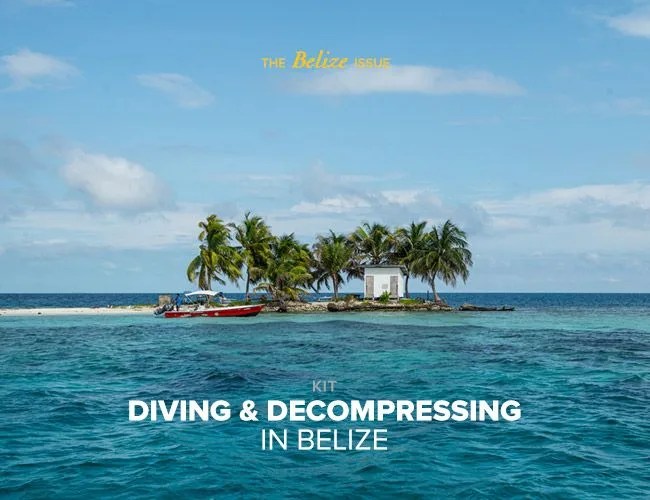

This surface interval was different though. After a long and fairly uneventful dive on an unnamed reef out in South Water Caye, I clambered aboard Splash Belize’s dive boat, shed tanks and weights and stripped off my wetsuit. The big diesels rumbled to life and Captain Malcolm steered toward a small island in the distance. “Island” may be an exaggeration. The cayes (“keys”) off the coast of Belize consist of tiny mounds of sand with a coconut tree or two sprouting from them, most smaller than a typical suburban backyard. As we drew closer to this one, I could make out a few small panga boats and some activity on the beach. Then came a distinctive smell: barbecue.

Our boat anchored a ways offshore and a panga ferried us to the beach, running up on the sand dramatically. There was another dive boat anchored nearby and, with the arrival of our group, the island took on the feel of a crowded cocktail party. The island, about an hour from the mainland by boat, was used by fisherman as a place to take shelter or camp out while on the sea all day. A massive weatherbeaten grill sat at one end and a small shack with a toilet stood at the other. In between were picnic tables under the sparse shade of a giant coconut tree. A smiling Garifuna man was tending the grill, flipping blackened chicken pieces with a long set of tongs. He had arrived earlier in the day on a small boat with a load of charcoal and coolers of food — chicken, potato salad, fruit and chips. It seemed almost too good to be true, I thought, as I brushed aside a hermit crab and sat down to tuck into a heaping plate of food. The afternoon’s dive could wait. I was hungry.

Belize’s reefs are healthy and swarm with rays, sharks and grouper along with the usual array of technicolor reef fish — wrasses, angels and parrotfish.

Underwater, the Caribbean looks much the same whether you’re diving in Belize, Mexico or Bonaire. It’s topside where you get a real sense of place. And Belize is a rich place. Its diverse population — a stew of Mayan, Garifuna and Creole — consider themselves more Caribbean than Latin American. The British colonial influence is still seen here in the buildings, names and traditions (tea, anyone?). It’s a country of fewer than half a million inhabitants, yet it’s filled with some of the richest biodiversity and pristine jungles and reefs in the world. Belizeans value their wild assets: more than a quarter of the country’s land is set aside for national parks and wilderness reserves. For these reasons, Belize has become a favorite adventure destination in Central America.