The Olympic Games are important for many reasons. They are historical, a modern day analogue to the great Ancient Games millennia ago. They are monumental: this year’s Winter games in Sochi, Russia will feature 98 events spanning 15 sporting disciplines, involve 88 nations and cost over $50 billion American dollars. They are also symbolic: a unification of countries that supposedly sets aside any political difference in the name of friendly competition (friendlier than war, at any rate). But the Games are also absurd, and the Winter Olympics especially so. The cold weather sports show includes everything from what is basically fast group-sledding, something we’d call “The Ice Capades” in any other context, screaming while sweeping in front of skidding stones — and need we mention the outfits?

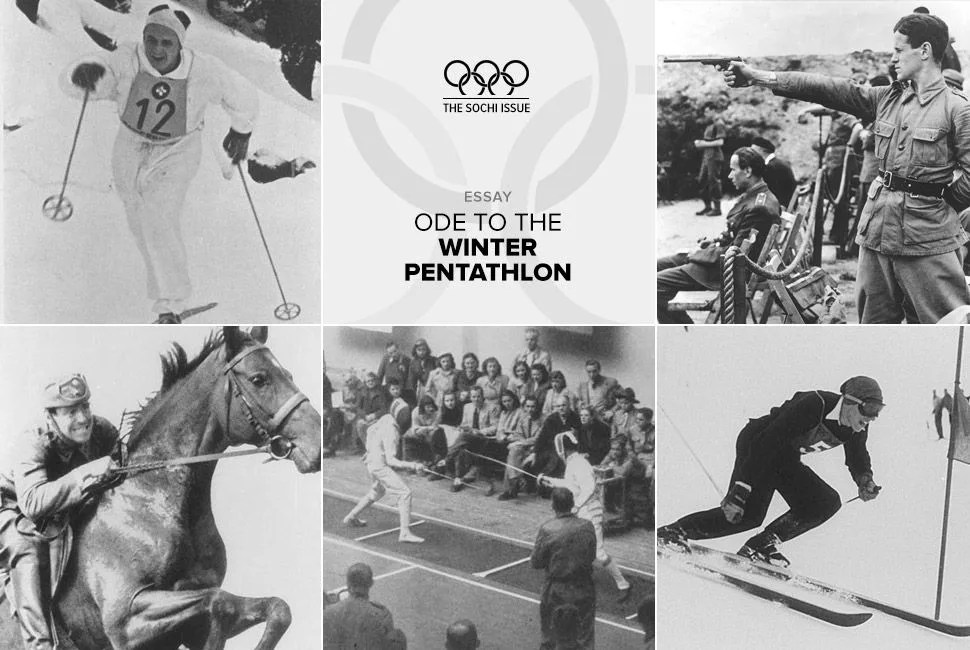

But in the history of the Winter Games, the most spectacular, over-the-top event to take place was a one-off: the Winter Pentathlon at the 1948 Winter Games held in St. Moritz. There may never have been a more elitist combination of athletic feats grouped together at one time before that fateful winter, and there likely hasn’t been since. A winter pentathlete in 1948 did the following in rapid succession: cross country skiing, shooting, downhill skiing, horse riding and…fencing. Of course there is scant footage of the event in question, but one likes to imagine the bravado with which a skiing fellow might snow plough to a stop next to his trusty steed, and quickly secure his rifle and scabbard before setting off into the fresh Swiss powder. The thing is well-endowed with pomp and prep school polish.

We love it. We long for it. We want it back.

We’re also quite enamored with the history of the pentathlon itself. It was in Stockholm in 1912 during the fifth Olympiad that the five-pronged gauntlet was reintroduced as an event that “tested a man’s moral qualities as much as his physical resources and skills, producing thereby the ideal, complete athlete”, according to the founder of the modern olympics, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the same man who said that the pentathlon was accepted back into the games after the “Holy Ghost of sport illuminated my colleagues and they accepted a competition to which I attach great importance”. This is a compelling thing to say. Of course, those games were in the warmer months, so swimming and running were substituted for the ski portions. But we say without the snow and snowsuits, without the horses galloping through snow like they’re off through the woods to grandma’s house, without the firing of weapons like arctic assassins, without the fencing sandwiched between snow sports…it’s just not the same.

The spirit of the original sort of lives on in the tradition of the modern pentathlon, the winter biathlon and in triathlon events (we’re waiting for the winter triathlon with fat bikes), yet it’s that one winter pentathlon that grabs our hearts and imagination. Yes, the bizarre showmanship attracts us — the thing was hard as hell, too. The idea was to test the skills required of an archetype soldier of the time, which meant physical mettle, yes, but also technical skill, composure and determination. Brass balls. These guys were jacks of all trades, masters of all. In an era that seems to prize specialization over adaptation, the 1948 winter pentathlon is a good reminder of how impressive it is to be good at many things, even when it’s snowing.