19 photos

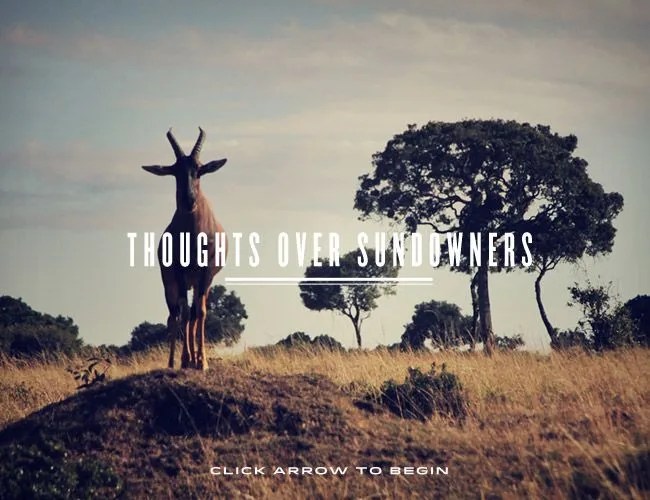

The Masai Mara National Reserve on Kenya’s southwestern border with Tanzania is blanketed with large mammals, so heavily in fact that it takes a day or two to register that the animals are real and not holographic or cutouts from a National Geographic photo spread. This is what happens when you combine a life spent mostly staring into a computer with the ease of international travel. One day I’m in Crown Heights, Brooklyn; 24 hours and four airplane meals later, I’m on safari in the African savanna. The rapid change of scenery can give vacation a dream-like quality. What unsettles the reality principle further is that the animals stare right back at our vehicle, look right down the barrel of my lens for a good long while before scuttering off. I feel like the animal. It is the antelope that watches me.

MORE SWEET TRAVEL: Exploring Actun Tunichil Muknal Cave | Harvesting Champagne | 72 Hours in Edinburgh

Chief among the gawkers are giraffe, who as the tallest terrestrial animals are exceptionally fit for surveying the lay of the land, and the wildebeest, the most abundant mammal in East Africa and also the least visually appealing, with a jerky half-sideways gait and a devilish face. This animal is known in the safari community for its annual migration: What happens is that every year more than a million wildebeest, joined by zebra and other antelope (of which the wildebeest is one) move in a clockwise direction from the Serengeti in northern Tanzania, up into the Mara, and then back down again. It’s one of nature’s great symphonies, plus lots of the wildebeest give up the ghost to lions — so there’s something for everyone.

The wildebeest is so silly looking it’s tempting to hop out of the vehicle and grab it by the chin, which is discouraged for reasons of personal safety and just common decency. But even if nobody (else) is talking about it, somebody must be thinking it. Because physical contact with the animals, on many different levels — studying them, showing them off, protecting them from poachers, protecting visitors from injurious contact with them, land appropriation and management issues — is, after all, the central component of this whole safari business. It (the desire to touch or even tackle said wildebeest) also hints at a fundamental question that is no doubt vexing Hemingway readers and admirers of the great and swashbuckling President Theodore Roosevelt:

Will there be blood?

8 photos