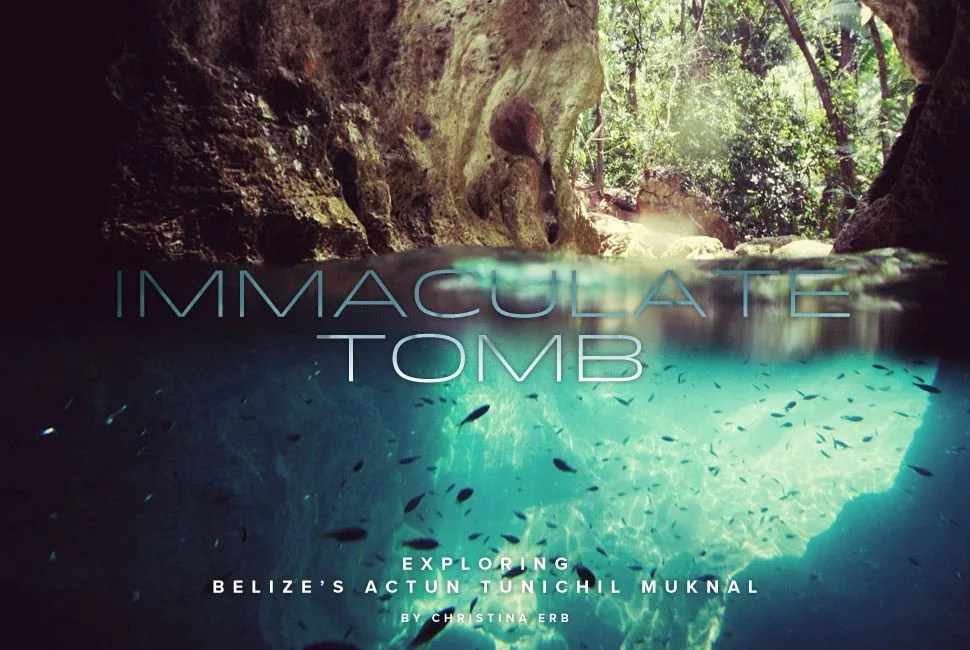

In the Tapir Mountain Nature Reserve of Western Belize, late in 1989, Dr. Thomas Miller jumped into a tributary of the Roaring River and swam inside an unnamed cave’s vine-covered mouth. The American geologist wasn’t in pursuit of a lost Maya relic; he was there to study geomorphology: the formation of caves. What he found, however, led him to contact Dr. Jaime Awe, director of the Belize Institute of Archaeology, who recorded his findings in 1992.

The cave’s twisting river, in places neck deep, wove underground to an elevated cavern filled with the skeletal remains of 16 human sacrifices, ranging from infants to mid-40-year-olds. And, in an upper, farther recess of the cave, a slender skeleton lay calcified to the cave floor amidst bat guano and predatory spiders.

“It struck me at my core. It was unlike anything I had seen before. We always want to think we’re immortal, but the human remains in this Maya ritual cave site reminded me how fragile we humans are,” Awe said. “I thought to myself, ‘Why should archaeologists be the only privileged people to see what happened here 1,100 years ago?’”

Awe took a self-described gamble and opened the cave five years later to the public with little to no regulations or infrastructure to preserve the relics inside. He hoped tourism would repel looters. To the surprise of international archaeologists, it’s been, for the most part, a raging success.

I first heard about the Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) Cave in 2011. Heavily shadowed photographs of a complete adolescent skeleton — known falsely as the Crystal Maiden — coupled with descriptions of the narrow river that winds through pitch darkness to an open cavern led me to believe it was indeed a Maya ritual site undisturbed by the 21st century. Still, I assumed that like most ancient ruins in the United States and across Europe, the mystique of the cave would be tempered by preservation and safety regulations.

But Belize isn’t Europe. The country, home to 327,719 people, has the lowest population density in Central America. It wasn’t until 2003 that it experienced a significant increase in tourism — jumping from 199,521 to 220,574 overnight visitors per year. It has remained largely ignored by international travelers, history enthusiasts, and archaeologists. Awe estimates that only 10 percent of Belize’s caves and Maya ritual sites have been discovered and explored.