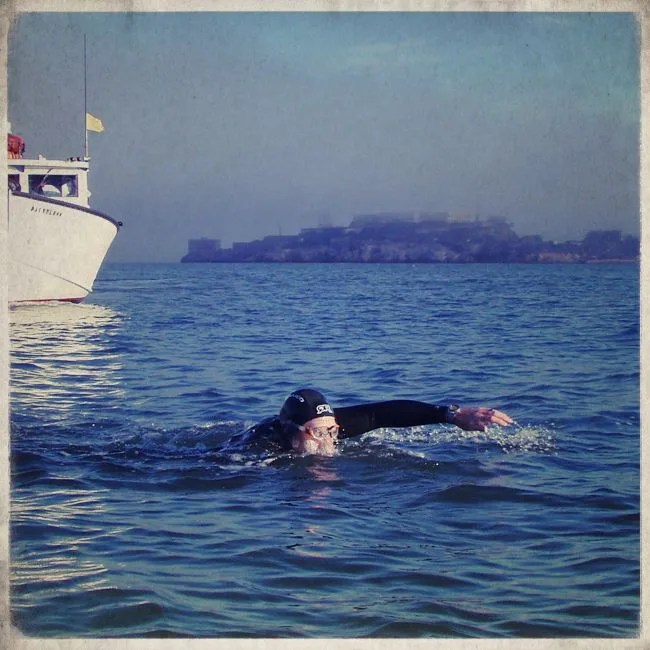

Bobbing in the middle of San Francisco Bay, I panted as I treaded water. My arms were turning to rubber and the wetsuit was chafing my neck. I needed to stop for a rest. My friend and kayak pilot, Kevin, paddled over and said, “Good job, you’re almost a third of the way done.” Really? Only a third? From my water-level view, the marina looked at least as close ahead of me as The Rock did behind me. A chill colder than the 58-degree water ran up my spine, and that’s when I felt that I might not be able to make it.

I must have watched Clint Eastwood’s moody Escape from Alcatraz ten times when I was a teenager. More than Clint’s cleverness and the usual prison-movie shenanigans, I was struck by the haunting foghorn, the searchlights and the men’s uncertain fate as they pushed off from the island in the dark cold water. Never did I imagine then that I would be jumping off a boat at that very spot on a chilly October morning and swimming to the city across the bay. But having done the usual bucket-list items like climbing mountains, running a marathon and diving with sharks, I was looking for a new challenge. Swimming across San Francisco Bay from Alcatraz seemed like a good one.

Alcatraz was once America’s most dreaded prison, where all of the most dangerous criminals were sent. The Rock was thought to be escape-proof. Once a prisoner got out of his cell, past the guards, over the wall and the fence, he faced the long swim. No one is sure if Frank Morris, the man Eastwood played in the movie, survived his escape attempt. I’d like to think he did.

Looking to my left, I saw the sun coming up behind the Bay Bridge, turning the choppy water to blinding gold. To my right, the lower ramparts of the Golden Gate Bridge were shrouded in fog and as I turned back to look at where I started, I caught a last glimpse before the island prison disappeared in a cloud. The slack tide was starting to move, pulling me out of the bay and into the Pacific. It was time to get swimming.

On paper, swimming from Alcatraz isn’t that daunting. The distance amounts to about a mile and a half, the equivalent of about 90 lengths of the pool at your local YMCA. Spend enough lunch hours putting in your laps, and the distance is doable. But factor in a strong current, waves, cold water, shipping traffic and San Francisco’s chilly weather, and Alcatraz is considerably more formidable. And then there’s the psychological challenge: what lurks beneath you in that dark, cold water?

Twenty-seven miles outside of San Francisco Bay lay the Farallon Islands, a favorite haunt of great white sharks, who are drawn to the area by the abundance of food in the form of elephant seals and California sea lions. Some say that San Francisco Bay is too polluted or too brackish for great whites. But there have been sightings. Only a year ago, a research group picked up a satellite tracking signal from a great white in the bay. And then, virtually overnight, all of the sea lions disappeared from their smelly perch at Pier 39, deserting the area. No one knows why. A new predator nearby? If you’re going to do the swim, you need to remember that shark sightings are very rare, and no one in the history of bay swimming has ever been attacked by one. You might get bumped by a 400-pound sea lion, but not a shark. Put it out of your mind.