From Issue Three of the Gear Patrol Magazine.

Discounted domestic shipping + 15% off in the GP store for new subscribers.

On a recent flight to Cancún, the row behind me was filled, three to a side, with five bridesmaids and one bride. They were all dressed in matching pink shirts and chatting loudly, involved in one big conversation. I could smell their bubble gum.

I was en route to Cuba by way of Cancún, which, at the time of writing, is one of the easiest ways to enter the country as an American. (Likely by the time you read this, major airlines — including American, Delta and JetBlue — will have begun offering nonstop flights to Havana from multiple American cities.) Cancún is a foil to Cuba; a decade after Cuba closed itself off, Cancún, which during the 1960s was a small fishing village, opened itself up. In 1970, extensive development began to convert the village into a resort town. The city now supports a population of over 600,000 and is synonymous with foreigner-filled beaches and parties brimming with cocaine and salt-rimmed drinks. The man at security in the airport, seeing my destination, had advised me not to drink too much tequila.

Basically: get down there before the girls seated behind me choose to swap Cancún for Havana. That’s the fear.

My visit to Cuba came on the heels of headlines that, using words like “tourism hell,” concluded that you, an American tourist, should get down to Cuba before American tourism changes everything. The final paragraph of a travel guide from The New York Times that I had skimmed just before takeoff read: “But as with all of Havana, the moment to go is now; in the world of Cuba that caters to visitors, change is here and accelerating.”

Basically: get down there before the girls seated behind me choose to swap Cancún for Havana. That’s the fear. That the Authentic Havana Travel Experience® will be sullied by a bunch of people on “vacation,” spending a lot of tourism money and searching out another beach of some fill-in-the-blank destination. A sun-spotted green screen that they can soak in vomit, semen and cheap beer. I was among this first wave of American dollars set on seeing things as they were, and maybe as they will be.

In Cancún, the check-in line for the 3:05 p.m. flight on Cubana de Aviación was almost completely full of packages. Two of my fellow passengers were systematically inching forward dense, plastic-wrapped cubes of novelty t-shirts and those vacation fedoras that seem to materialize on everyone’s head as they exit the terminal. What couldn’t fit in line was stacked to the right, a solid block of televisions, fans and air conditioners the size of a stretch limo.

It’s “like this all the time” at Cubana de Aviación, according to the man behind the check-in counter. Later I’d find that these air conditioners can be sold on the black market in Cuba for close to $800.

The first thing that hits you after you land at José Martí International Airport and clear customs is how fertile the country is — everything is the lush green of leaves or the red of tilled farmland. The second thing is the smell of gasoline. Any time you are in a car or near a road in Cuba, the cough of a 60-year-old exhaust system will envelope you. My cab driver, who wore pre-faded blue jeans and a gold-colored watch and chain to match his button-down shirt, tuned the radio to FM 87.5. So, as we passed a donkey carrying two men and some produce, Tyga’s “Stimulated” boomed from the cab’s open windows, announcing to the whole countryside that the rapper was gettin’ big, puttin’ in and penetratin’.

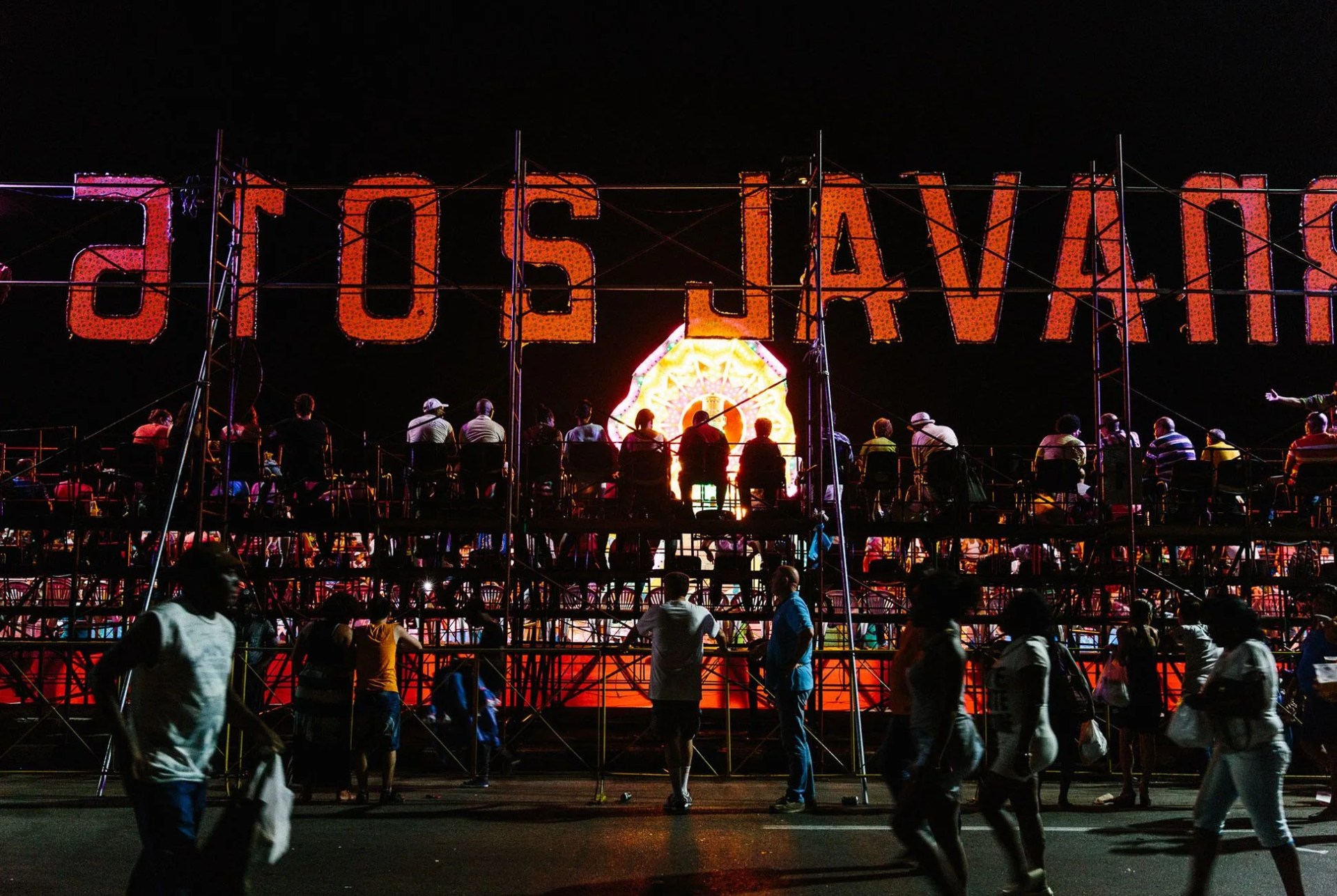

My photographer and I sat in traffic on the way into Havana. The source of the congestion was the Carnaval de La Habana, which is the little sibling of the Carnaval de Santiago de Cuba, itself a watered-down version of the Rio Carnival in Brazil. Bleacher seating for the parade was in place along the Malecón, a five-mile stretch of road and walkway that forms the city’s seawall and looks north toward the Straits of Florida and, in about 90 miles, Key West. On most nights, trios of men with guitars and drums, prostitutes, and women selling roses prowl up and down the Malecón. Their customers are a mix of tourists taking selfies while the sun sets and locals drinking 4 CUC bottles of rum (one CUC, or convertible peso, equals one USD). It’s the only place in the city with a relatively cool breeze. On this night, the Malecón was packed.

My photographer asked the driver if it was safe to bring camera equipment into the festival. The driver waved his hand.

“There will be more cops than Cubans at the festival,” he said. We thought he was kidding. He wasn’t.

The probability of a Cuban dying between the ages of 15 and 60 is less than in the United States, even though the US spends almost four times as much per person on healthcare.

Havana is a very safe city. According to a 2014 report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Cuba had a homicide rate of 4.2 for every 100,000 inhabitants, less than the rate in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This is a huge boon to tourism, especially when vacationers view Cuba versus the rest of Latin America, where the average homicide rate tops 25 per 100,000 inhabitants.

The primary reason for this safety is that the country is a communist police state, but there are less tangible reasons as well. When Castro came into the city in January 1959, took up residence in suite 2324 of the Habana Hilton (now the Habana Libre), and started taking private property for state use and nationalizing sectors, he revamped the island’s education and healthcare. Now, 57 years later, the probability of a Cuban dying between the ages of 15 and 60 is less than in the United States, even though the US spends almost four times as much per person on healthcare. And the country boasts a higher literacy rate than the United States. An educated, healthy and largely drug-free population means you’ll see tourists march down alleyways with cameras swinging from their necks, without pause.

Wanting to see for myself, at the end of the first night I headed into Centro Habana, which is one of the more run-down areas of the city. I emerged bored and with an ice-cream cone from a corner vendor.

Story Continues After the Photos

Emiliano Granado

Emiliano Granado

The next day, a man named Louis, who had a great ‘fro and knock-off Ray-Bans, approached us. You meet a lot of people like Louis if you look like a foreigner in La Habana Vieja, known more commonly to tourists as Old Havana. If you’ve seen a photo of an old car next to classic architecture, it was taken here.

Without a reliable internet, it’s easy for tourists to reach the limits of the omnipresent Lonely Planet guide to Cuba. Which is why improvisational amatuer tour guides like Louis exist. Some of these tour guides work for established international companies with divisions in Cuba. But many people employed on low state salaries turn to side jobs in the growing tourism industry. Some of them are park cleaners; some of them are lawyers or doctors.

Things we got from Louis: a tour of a ration store; a tour of a Santería store; a tour of a marketplace (it was Fidel’s birthday so everything was half off); a total of six mojitos for 6 CUC each (all ordered by him); a box of fake cigars; the internet.

As of July 2015, the Chinese telecom company Huawei placed a total of 35 hotspots throughout Havana for internet access. There are maps that mark where the hotspots are, but anyone walking around the city will eventually bump into dozens of Habaneros sitting on the curb or standing around looking at their phones, with a few tourists and their laptops peppered throughout the crowd.

Cubans must spend 2 CUC for 60 minutes of internet access. That’s 8 percent of the average Cuban’s monthly income, according to Cuba’s National Office of Statistics.

There is no public cellular data service in Cuba. Getting online requires an ETESCA card, which costs 2 CUC — but most tourists will buy them for 3 CUC from what I like to think of as “wi-fi dealers.” Louis pointed us to the wi-fi dealers that hang out on the first floor of the tenant building next to the Inglaterra Hotel, a centrally-located, wi-fi-enabled hotel.

Limited access is a matter of state control; Cuba is richer than neighboring countries such as the Dominican Republic and Jamaica, but fewer of its residents can get online. Most Cubans at the hotspots were using the internet in ways that are unexciting to Americans, but fantastically new in Havana: video chatting with relatives, reading about international news, posting to Facebook. However, the internet is heavily censored. Cubans use sites like EcuRed, a Cuban-built online encyclopedia, in place of Wikipedia.

But the biggest censorship to the internet in Havana is limited access. Besides having to go to where the internet is, Cubans must spend 2 CUC for 60 minutes of access. That’s 8 percent of the average Cuban’s monthly income, according to Cuba’s National Office of Statistics (although a marketing firm recently found that over 50 percent of Cubans earn more than 50 CUC a month).

Such barriers to access would spark protests in a place like New York City. No such visible demonstrations were happening in Cuba. One reason is police control. Another was put to me by our Cuban cab driver, who was an open critic of Cuban politics: The government is slow to make any changes because there is no threat of revolution. People are poor, but not poor enough to risk the consequences of protest.

“I’d say ninety-seven percent of the time, anyone who wants to have a genuine conversation with you about Cuba is not the one who just approached you on the street,” said Hannah Cohen, an American-born stringer and entrepreneur who has been living in Havana for the past few years, over lunch. Through her tour company, Cuba Rising, Cohen facilitates “genuine” experiences for her clients, typically American businesspeople, so that they can step off the plane, cut through the touristy noise and immediately start “making black beans in [their] new surrogate Cuban grandmother’s kitchen.”

“For the past fifty-six years, Cuba has said, ‘Fuck you,’ to everything the US has offered. That’s not changing.”

Part of Cohen’s job is also showing businesspeople potential investment opportunities. This is the hypothetical pregame to the bridesmaids’ beach party: the resorts come, then the tiki bars, then the crowds, then the nebulous “erosion” of local culture, to be replaced by buffet tables and sleeping in. And while investment in Cuba is not as attractive as investment in other countries due to governmental regulations and taxes, the government adopted a new foreign investment law in 2014 that cuts the tax on profits in half — from 30 percent to 15 percent — and explicitly allows foreign ownership.

An article in the New York Post with the headline “Celebrities and Rich People Plot to Turn Cuba into Tourism Hell” features a photograph of Cohen at the beach with a Boston-based businessman. Similar articles decry the swiftly developing investment-consulting arms at Cuban tour companies that are aimed at Americans. But a stance against all investment is also an open invitation for stagnation. The question is: how against the interests of normal Cubans is outside money?

We were eating with Cohen at Café Presidente, a privately owned restaurant in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana. This restaurant couldn’t have existed before 2011, when the Cuban government allowed some 200 types of private businesses to operate outside of state control — including hairstyling, carpentry and restaurants. The entire staff was made up of local Cubans. They were all making more money than they had in prior jobs, and more money means the ability to express themselves and build a culture — in this case a part of the widely publicized “culinary revolution” of Havana — where before there was scarcity.

“For the past fifty-six years, Cuba has said, ‘Fuck you,’ to everything the US has offered. That’s not changing,” said Cohen. She then conceded that “things have changed to some extent on a state level . . . but ninety percent of Cubans you talk to will say they haven’t felt a change these past five years.” And the government tends to agree; as recently as September 2016, Cuba’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bruno Rodriguez, stated that the easing of the US trade embargo has had essentially no positive effect on the country’s economy. (Although this comment was given in the lead-up to a UN vote on condemning the embargo, an annual blaming of US sanctions for the country’s problems, of which the Cubans we spoke with had grown wary.)

Story Continues After the Photos

On my final day in Havana, I walked around 331 Art Space, a gallery created by Frank Mujica, Alex Hernández and Adrián Fernández. The trio attended one of the island’s only art schools together, and have found considerable national and international commercial success. They attribute this success, in large part, to entering the art world together, but also, with the slow opening of Cuba, more interest from galleries that see coverage of their work all over the world.

As a part of the generation in Cuba that’s starving to push things forward, especially now that regulations have begun to relax across the country, they talked about change in Cuba as a force for making things better. Fernández pointed to a series of four prints arranged in a two-by-two grid. They were part of his Roystonea Regia series, and each was a rendering of the Cuban royal palm tree — taken from a small sliver of a Cuban postage stamp and blown up to the size of a dinner plate.

“You put a stamp on an envelope and send it out worldwide. It’s an official record,” said Fernández. “The palm tree is a national identity in Cuba.” But by photographing and then expanding the size of the trees by 100 times, Fernández had distorted them. “You almost have to turn your eyes in order to see it,” Fernández said. “You realize it is manipulated.”

Next to the stamps, Fernández had a photograph of a dancer from the Tropicana night club, a nightlife spot that was taken over by the government in 1959, and is still open to this day. The woman in the photograph, half her actual size and dressed in a dancer’s costume, was saturated with color and lit from every angle — a caricature of a decades-old tradition.

Some older Cubans, especially those who left during the “Special Period” in the ‘90s, which was full of scarcity after the Soviet Union collapse, react negatively to his work. Their reality was different, he says. And their art reflected their hardship.

In the past few years, the three artists have traveled to Germany, Sweden and New York to show work in galleries. They are part of the “new Cuba,” showing that Cuban art can compete on the world stage. In this way, despite having zero interference from the Cuban government, they are political statements just by existing.

“We see ourselves as artists first,” said Fernández. “We do not like to project ourselves as the poor islander-artists of Cuba.”

After 331 Art Space, we grabbed a ride with Fernández to El Cocinero, a new, hip restaurant in the westernmost part of Vedado, away from Old Havana. El Cocinero and its neighbor, Fábrica de Arte Cubano, are supposedly where the cool young Cubans go to experience the revolution in food and culture.

My dinner — which was an Old Fashioned made with Kentucky bourbon, a crab-and-sweet-potato appetizer and sesame seed-encrusted tuna entrée — came out to about 30 CUC, a month’s salary for many Cubans. Looking around, I saw that most of the guests were foreigners, taking selfies from the upper balcony and speaking a variety of European languages. Besides the waitstaff, I saw none of the familiar faces of the Cubans I had been spending my days with.

For the cab drivers in Habana Vieja, the artists in Miramar and the waitstaff in Vedado, life in this “new Cuba” seemed to be getting easier. But just how much trickles down to help everyday Habaneros is yet to be seen. For the tourist, getting down to Cuba before “everything changes” means going down before “new Cuba” hits its stride and leaves behind the scarcity of “old Cuba.” Bridesmaids be damned.

Read More in Our Magazine

A version of this story appears in Issue Three of the Gear Patrol Magazine, 320 pages of stories, reports, interviews and original photography from five distinct locations around the world. Subscribe Now: $39