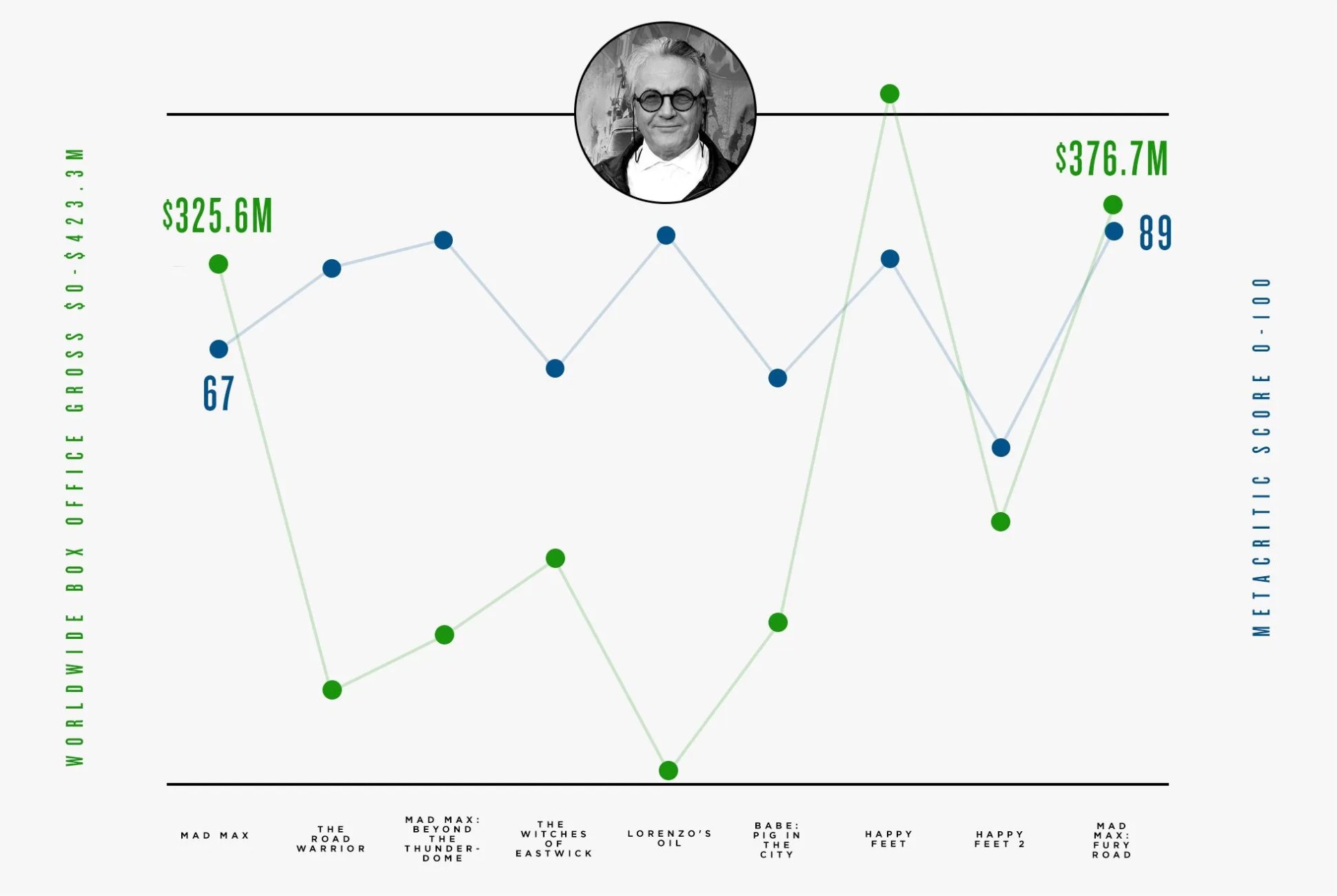

Age: 70

Birthplace: Queensland, Australia

Year of First Feature: 1979

Number of Films: 9

Average Metacritic Score: 72.2

Worldwide Box Office Gross: $1.7 billion

Total Oscar Nominations: 6

George Miller has two very different audiences. One giggles at dancing penguins. The other giggles at paint-huffing maniacs, buggy racing their way through an apocalyptic sandstorm, blowing each other to smithereens along the way. The connection between the two — the ‘Happy Feet’ and ‘Mad Max’ franchises, respectively — is Miller’s incredible ability to make both animal hip hop and apocalyptic survival straightforward, believable and fun. That kind of turning the complex and subtle into the gloriously simple is a tough thing to pull off. It brings incredible films, like Mad Max: Fury Road, to life.

At 70, Miller is the oldest director nominated by 18 years. He was 34 when he made Mad Max in 1979 on a budget of $350,000 (he paid the bills not as a waiter or barista, but as a doctor). The film’s style, its unabashed deep dive into a violent punk world with obvious nods to Western, made it an instant cult classic, and, after mixed reviews, eventually brought it immense box office success. Miller made two more Mad Max movies, both with the same spirit as the original and Mel Gibson’s grunty personality. He went on to direct a mainstream Hollywood flick, The Witches of Eastwick, in 1987, and a critically acclaimed drama, Lorenzo’s Oil, in 1992. Then, a pivot: children’s movies. He cowrote Babe, then directed Happy Feet, Babe: Pig in the City and Happy Feet 2. “Even my mother said, ‘When you started making the Babes and Happy Feets I thought you were calming down,’” Miller told NPR. “But then she saw the latest, Fury Road, she said, ‘Sometimes I wonder what goes on in your head.’”

Fury Road is a reboot, but it’s also a proof of concept. Miller needs no origin story, no dramatic rebirth of the franchise’s character and tone. There need be only former cop Max Rockatansky, still reeling from the death of his wife and daughter in a postapocalyptic world. Only other would-be heroes out there, struggling. Only souped-up buggies, war wagons and motorcycles, and the nuts who careen them. Miller put these players on a linear path from point A to point B and back to point A; he kept dialogue sparer than the roll cage of a war buggy; he captured the frenetic chaos of the film’s continuous car chase using real effects rather than superfluous CGI, because “it’s real people in a real desert; there’s no men in capes flying around or space vehicles and so on.” The New York Times called it “imaginative discipline” in their review, and they got it exactly right.

These simple factors combine to make Fury Road feel like a pure snort of action movie adrenaline after years of stuff cut with laxative. Its literal explosions are so big that the figurative ones — like the notion of a female protagonist (Furiosa) in an action movie — don’t make you think twice. But to Miller, it was easy. “The thing that’s in conflict is human and female,” he told NPR. Simple as that.