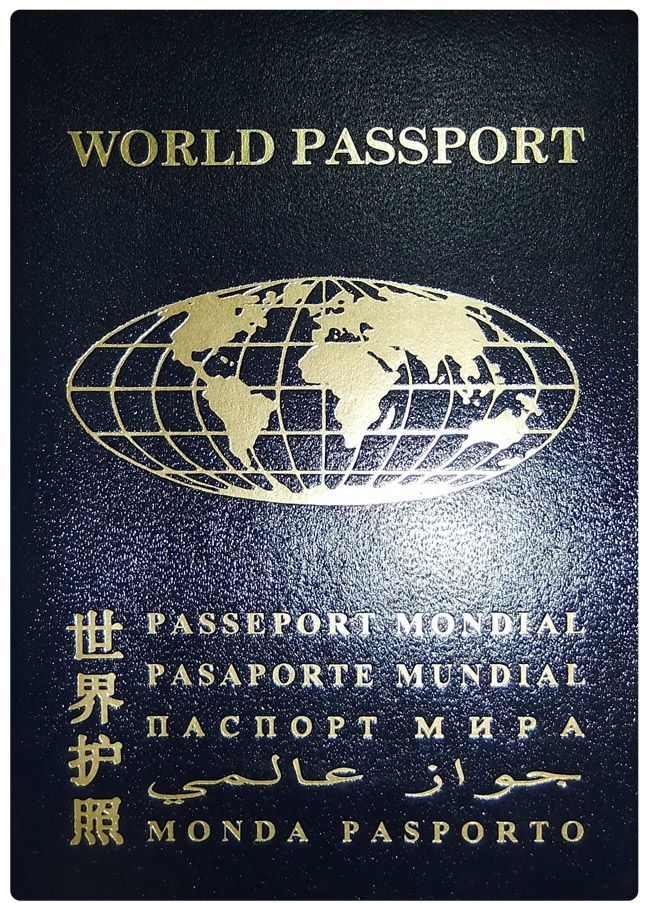

When rapper and actor Yasiin Bey, formerly known as Mos Def, was arrested on January 14 in Cape Town international Airport for violating immigration laws, the passport he carried was not a traditional one. Bey, along with his wife and children, had been living in South Africa since 2013 on since-expired tourist visas; on the day he was arrested he tried to use a “World Passport,” a document created over 60 years ago by a single, similarly stateless man. The document, which has a deep navy cover with inlaid gold lettering, just like many traditional passports, failed to fix his visa issue. The South African government detained Bey and gave him 14 days to leave the country. He has since been released on bail and will be tried in a South African court in March.

In a half-spoken, half-freestyled audio statement on Kanye West’s website, Bey announced his retirement from music and acting, then explained his use of the document. “Anyone can do the research about the World Passport. It is not a fictitious document.” Bey is correct; the World Passport is a real document. What it is and how it works, in reality, involves some deeper investigation.

The World Passport was created in the 1950s by the late actor, activist and World War II bomber Garry Davis. After relinquishing his own US citizenship in 1948, Davis developed the concept of a World Government, and subsequently the World Passport, in an ongoing campaign for peace and the dismantling of national boundaries. The passports were aimed at providing refugees and stateless individuals (Davis included) identification as they traveled across national borders.

World Passports are administered in the same way to this day, providing an application and fee ($55 for a three-year activation period) sent to Davis’s Washington, D.C. nonprofit, the World Service Authority. There is also a background check for each applicant, says David Gallup, the organization’s chief attorney who, after Davis passed away in 2013, became the president and head counsel of the organization.

Gallup is jovial over the phone, and quick to assert that the World Passport is still a document used to successfully cross national boundaries. He attests to the six countries that officially recognize the World Passport (Burkina Faso, Ecuador, Mauritania, Tanzania, Togo and Zambia) and to the list of 183 countries, provinces and territories that have, at least on one occasion, recognized it by stamping it with an entry or exit visa. The passport has also aided in more contemporary crises. Gallup describes a recent incident in which one was issued to help a lesbian-identified Iranian woman escape persecution in her native country. Gallup also mentions that World Passports were issued to Julian Assange and Edward Snowden (while he was still living in the Moscow airport). Whether or not they’ve been used is not confirmed. “It wasn’t specifically for Snowden — well, it had his information on it, but it was really to make people aware and highlight the ridiculousness of nation-state borders,” says Gallup.

But the World Passport has its limits. Before Bey’s recent failure in South Africa, Davis, the creator of the passport himself, was regularly arrested while attempting to use it. Gallup also mentions incidents that he’s negotiated in the Netherlands and Ecuador in which government officials refused to recognize the passport. Furthermore, the current refugee crisis and the tightening of the visa waiver program prevent certain parts of the world from receiving passports at all. “The US government blocks countries like Iran, Sudan, Somalia and North Korea from receiving our services,” says Gallup.