15 photos

Downstairs at King Saddlery they’re making lariats on a home-made loom that resembles something out of Mad Max and looks as though its gears and pulleys and rubber tires are about to fall off at any second. Runs smooth as glass. It paces back and forth along the length of the concrete floor, tensioning and weaving strands that seem to be made only of increasingly smaller ropes down to the core, which looks like strings of DNA. In the corner is a home-made heat room — an oven, really — where the ropes are stretched and straightened so they’ll fly cleanly through the air in search of a horn or a back leg. Coils of polymer rope turn the floor into an ankle-breaking maze of concentric circles; dried wax clots the far wall where ropes receive their coating. This operation beneath the main saddlery floor turns out lariats (not lassos, please) for world-champion steer ropers, though it looks like the hobby den of some eccentric uncle who might have nefarious S&M underpinnings.

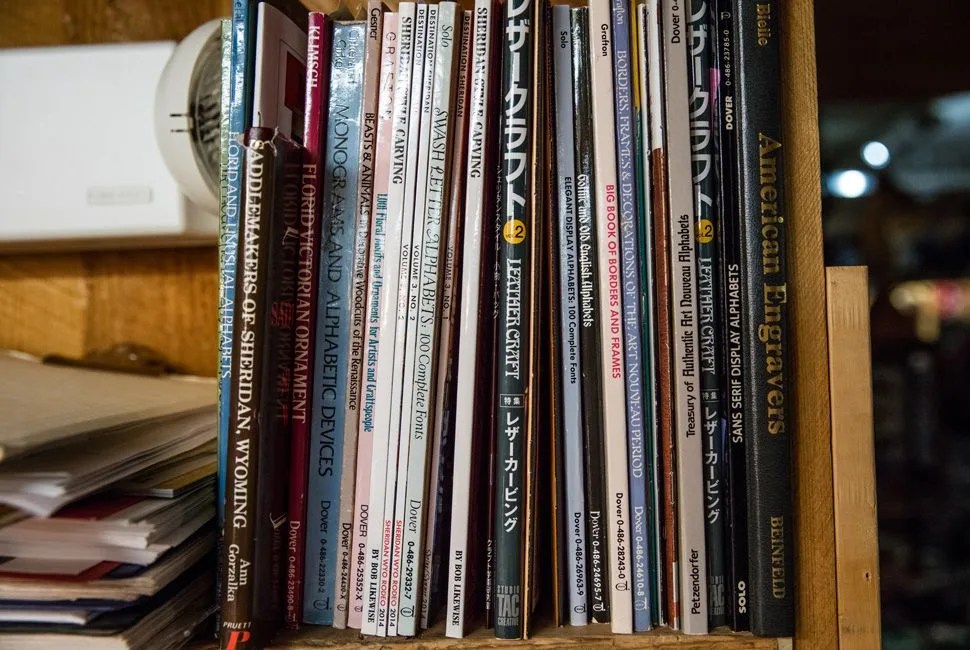

Saddle shops are supposed to be unexceptional hutches off dirt backroads that smell like old stable hay. King’s, a monolithic establishment in the downtown of modern, quaint Sheridan, population 17,000, has its own scent (tanned leather and fresh nylon); its own office space (it is enormous and warehouse-like, with hundreds of mounted animal heads peering down from the walls, a museum in the back and the hellshop-lariat-loom downstairs); its own reputation. This is an institution for farm implements in a state that’s zoned 91 percent rural. It seems King’s needs small-town Wyoming to exist, and Wyoming needs King’s, too. Without it, Wyomingites might have to use shit lariats, and might get second-best repairs on their saddles. They might never fully realize the potential beauty of their tools.

The mechanical engine downstairs makes an impression, but it’s the human engine that makes King’s Saddlery what it is. King’s, it seems, only hires savants. This might be why their name brings a knowing smile of envy from every Wyomingite we speak to, why their craft never strays from sublime art. Considering their main fare is ranching equipment, this is an unparalleled feat.

Upstairs, a nervous-looking man building a saddle on a lit workbench strains to lower his genius to my basement level of knowledge on the subject. You start with sizing so that the pommel… well the pommel, that’s the nub on a Western saddle… well yes, there’s Western and then English… no, no German that I’m aware of… well nationality is less important, I suppose… Finally I beg off the matter and ask how many he makes in a month. He settles on two to three a week, which is — here he hesitates for a minute before going on into self-compliment — very fast. The saddles are beautiful hulks, their layered guts of gleaming leather and simple stitches laid bare on the table. The army of them this man has assembled hang to the high ceiling on racks like the taxidermied trophies they face. Seeing a saddle made is like seeing a canyon carved by water out of rock in fast-forward. They’ve always simply seemed to exist, objects above creation, mined out of the ground fully complete. The man sews on, building a mount to last a lifetime or two.

King’s, it seems, only hires savants. This might be why their name brings a knowing smile of envy from every Wyomingite we speak to, why their craft never strays from sublime art.