Francine Shore, her straight, straw-colored hair reaching down to her shoulders at odd angles, held her hands together like she was about to bow her head in prayer. Instead, she looked up at me, her eyes wide, and she laughed. It was a full-bodied laugh, beginning in her diaphragm and erupting in a series of cackles and ah hah’s — like a detective making a breakthrough — while her head rolled back and forth, hair momentarily obscuring her eyes. Across from her, I sat in the same position, doing exactly the same thing. After a few awkward moments of forced cackles, the laughter became genuine.

That exercise was just a warm-up, an example of a typical greeting that begins the hour-long sessions that Francine leads three times a month in a rented studio overlooking The New Yorker Hotel. Her sessions then transition into dancing, controlled breathing, and improv — anything to get everyone loosened up and giggling. All of the exercises, from using bright and beaded props, to pretending to break an invisible vase, are part of laughter yoga, a two-decades-old therapy from India that attempts to capitalize on the many health benefits of laughing.

“We imitate life. Think of any situation and I can develop a laughter exercise: I’m late for something, so I’m jogging in place,” Francine said, her teal and fuchsia sleeves pumping back and forth by her sides. “I’m pointing to my watch, but I’m late anyway. So then I just let go and laugh.”

In her boyfriend’s Upper West Side apartment, where we met, Francine explained that she dislikes — she prefers not to be hateful — how laughter yoga is portrayed in videos. Short clips of the practice, aired on news segments or uploaded to YouTube, show strangers standing around shaking hands or pouring imaginary buckets of ice on each other. All the while they laugh in a way that could be mistaken for a flock of chickens, clucking in a farmyard. “If you actually watch the videos…it looks like a cult, loons, or something,” admitted Francine. “If you don’t go and see the science behind it, it does look a little crazy.” I promised I would.

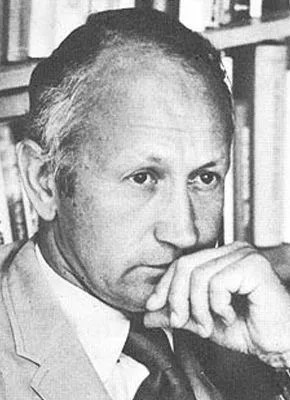

Laughter yoga had its genesis with Norman Cousins, the respected, longtime editor-in-chief of the now defunct magazine Saturday Review. In 1964, doctors diagnosed Cousins with ankylosing spondylitis, a type of arthritis that put him in constant pain. He locked himself in a hotel room and watched funny movies or read humor books in order to make himself laugh, finding his only solace in “10 minutes of genuine belly laughter [that] had an anesthetic effect and would give [him] at least two hours of pain-free sleep,” an observation he reported in his bestselling book Anatomy of an Illness, published in 1979. His acclaimed book ushered forward interest in the beneficial effects of laughter and put into the spotlight the close relationship between the mind and body.