10 photos

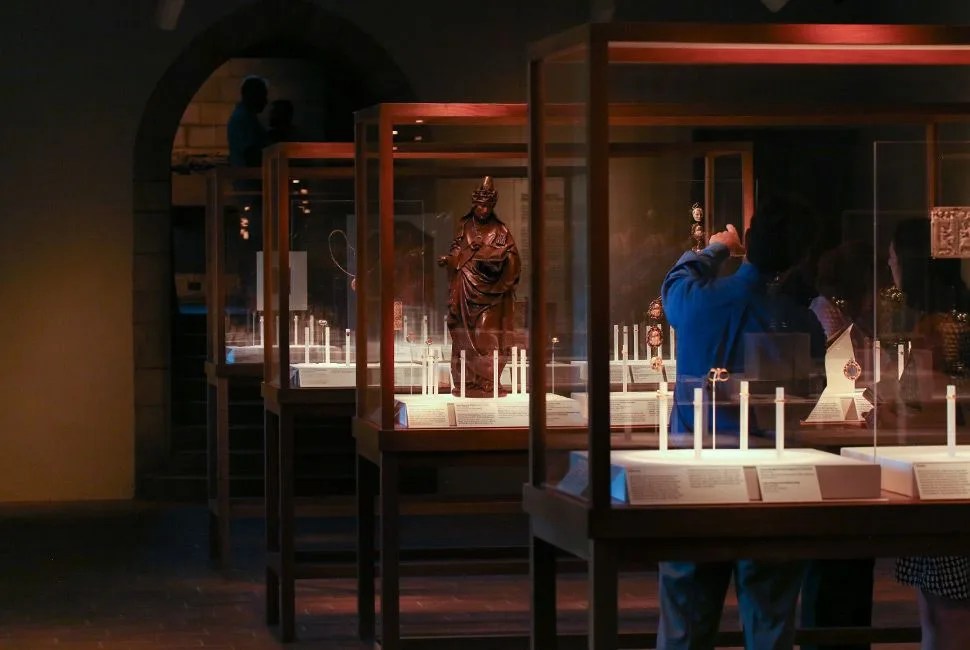

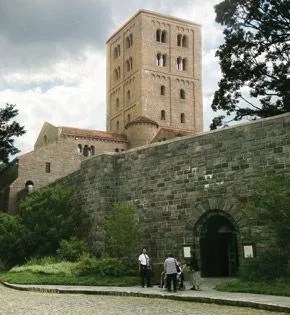

Stone walls surround courtyards filled with flora ranging from seasonal flowers to a hops plant. It’s quiet — the only noise, birds chirping. The place is charming, and if you hadn’t just endured an hour-long subway ride, you might forget that you’re in New York City entirely. The Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s slice of paradisal Europe in upper Manhattan, aims to transport its visitors to another era. “It’s funny,” curator Griffith Mann tells me, “The Cloisters is often a first-date place, and [we’ve] had a couple of proposals here, actually”. It’s not uncommon for guys to ask the Met to help them pop the question (they usually say “yes”). The romance of the Cloisters pairs well with the exhibit I’ve come to see, called “Treasures and Talismans”, which explores rings as they relate to status, life events, protection and identity.

I’m interested in rings as tokens of love, and the engagement ring is the most obvious example. But surprisingly, its origin can’t be pinned down precisely, and it hasn’t always had a diamond in it. As far as Mann knows, our association between diamonds and engagement is relatively recent — Renaissance-recent, at least — whereas the connection between the ring finger and love goes back to ancient times. People once believed that a nerve in the now “ring finger” turned into a vein and lead right to the heart. They called it the “venus amores,” the vein of love.

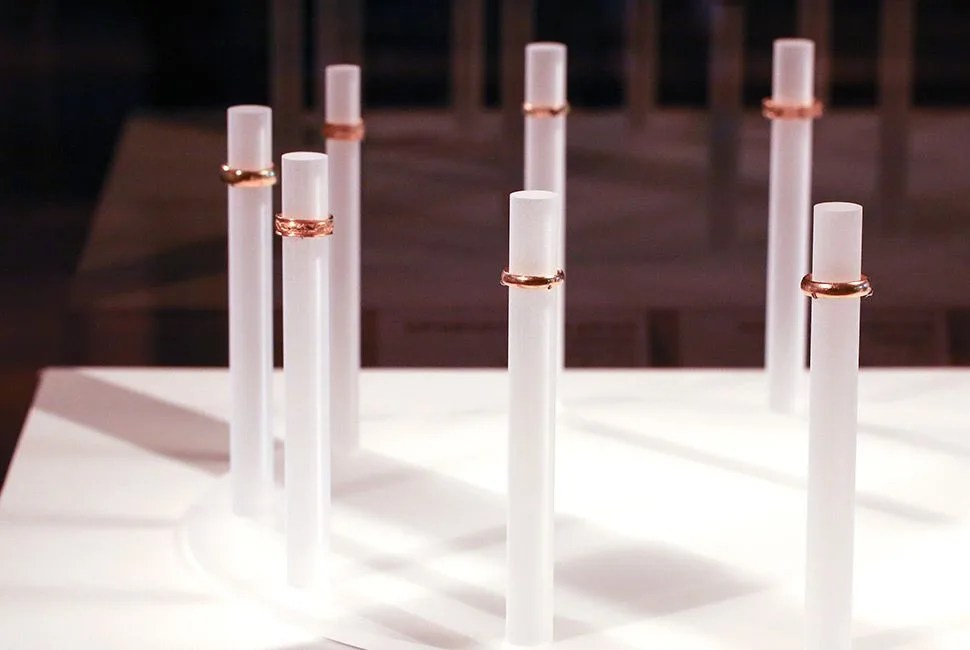

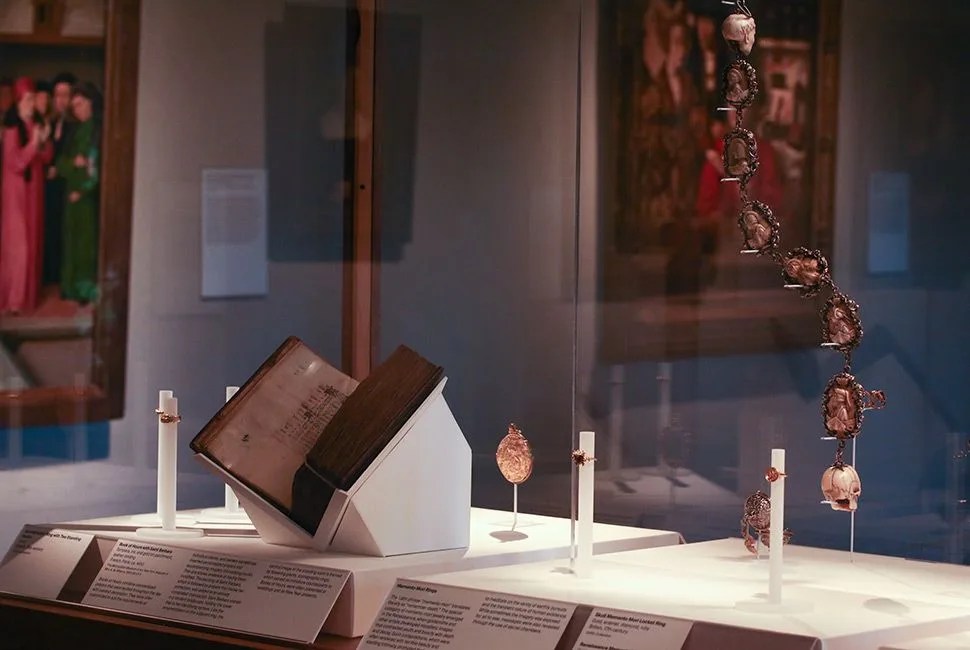

The exhibit moves through different categories of rings, accompanied by paintings from the Met’s other collections and even videos replicating ancient methods of goldsmithing. As early as the ancient Roman world — we’re talking single-digit centuries, here — people exchanged gold rings as tokens of affection. Gold was special: It didn’t tarnish, and it thus signified eternity. And, its ability to be melted down and repurposed made it versatile. Goldsmiths and their patrons usually sourced gold from coinage, or taking currency or other gold objects and melting them down and reusing them. One gold token, whose center hails from the first century, features an onyx cameo of three little cupids. It was made for a man, likely gifted by a loved one before a trip. If you would be separated from your beloved, you might get him or her (usually him) a token of protection or something to remember you by.

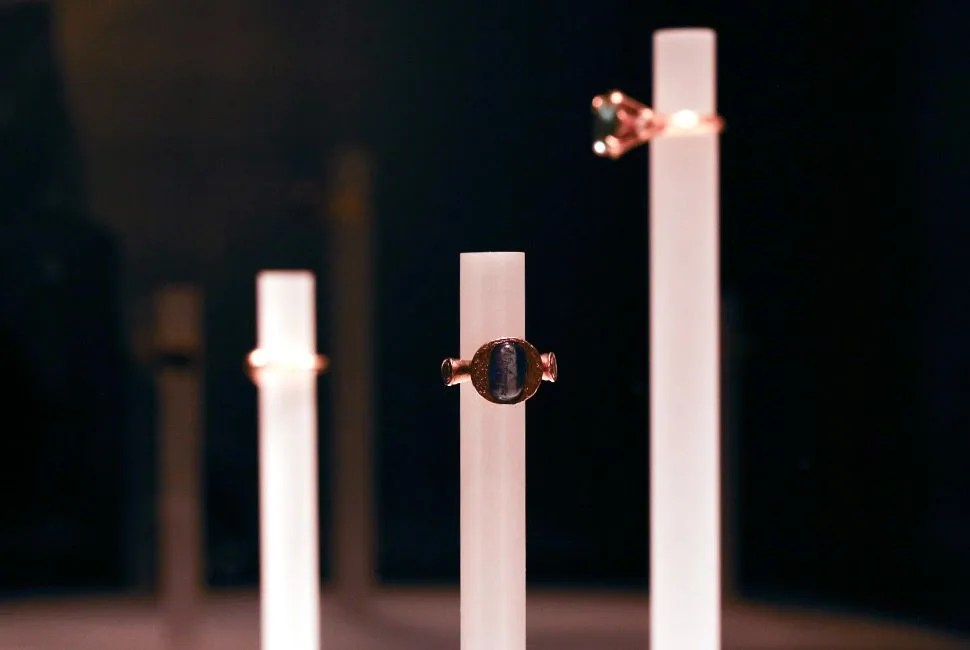

The rings most similar to modern tokens of affection are the first two of the exhibit, though they weren’t made for women or for an engagement or marriage. One ring, a gold-set octahedral diamond, is from Ancient Rome. There, diamonds connoted rarity even more than they do now, but they did not necessarily connote love or the commitment to marry. The ring’s purpose is unknown, and while the diamond appears to be cut, the technology for that didn’t exist until the 15th century; thus, the conclusion is the diamond is in its raw state. The ring alongside it is from the Renaissance. It’s a bezeled gem slice ring, a slice of garnet (believed to protect the wearer from evil) set in a simple gold band. Since the gem is sliced thinly, the gold reflects onto and through the gem.

The last case of the exhibit contains a 14th-century item that is surprisingly timeless. It’s a 14th-century writing tablet that displays a couple’s courtship, from the woman’s initial rejection to the eventual proposal. It is ivory on one side and wax on the other. It would have been used by lovers to send secret messages by carving them into the wax, then wiping them clean. It’s “the medieval version of Snapchat,” Mann tells me. While the app is new, the concept is not — the demand for ephemeral love communication precedes the digital age by thousands of years.