7 photos

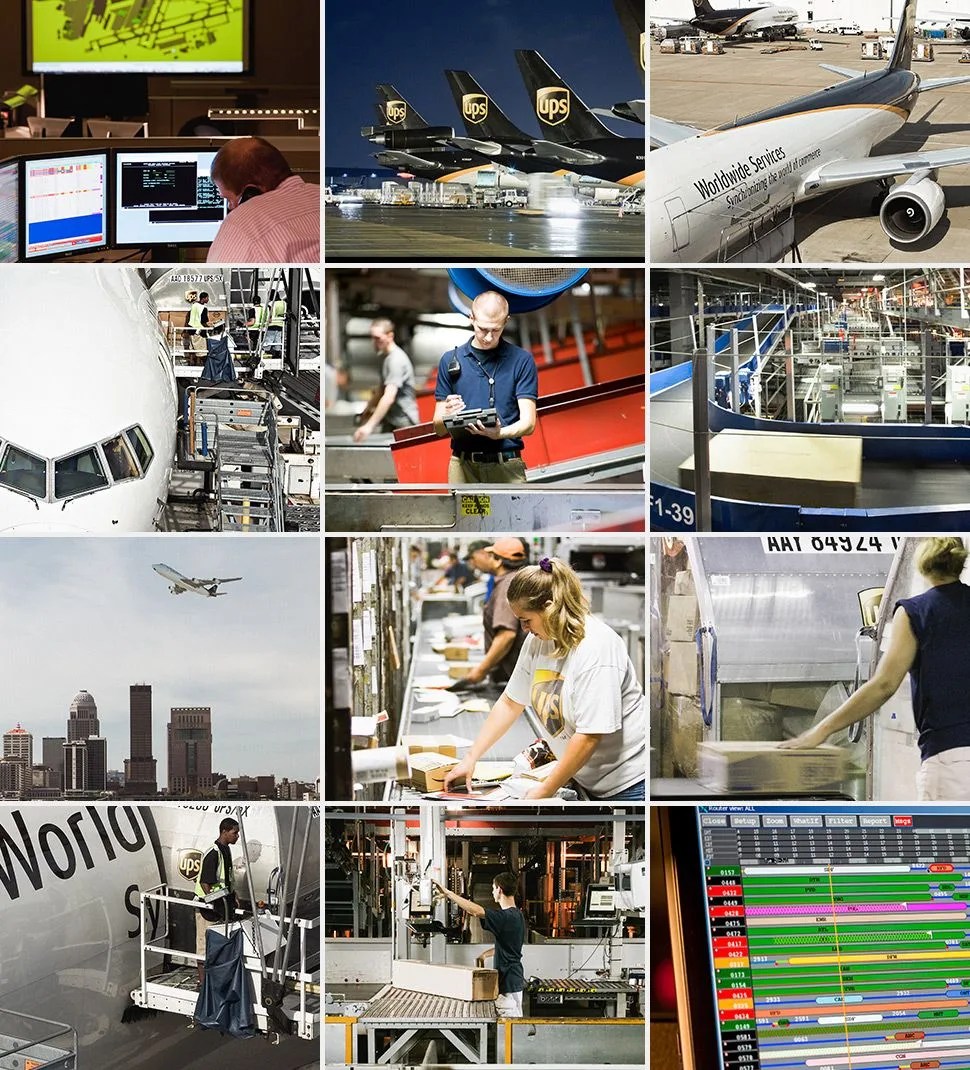

At precisely 2200 Zulu (7 PM EDT) on the night of March 31, we sit down with eight aircrew members and a coordinator around a long wood veneer table in a ready-room. A live speakerphone on the table adds meteorologists and maintenance and operations specialists from a nearby command center to the mix. A briefing ensues. Flight crews are given weather information via the meteorologists and a live CONUS (continental United States) weather map projected on a large screen across the room. Each crew member scans a preflight information sheet, which includes fuel status and weight and balance information for their assigned aircraft.

Moments before, we had been on the flight deck of a large twin-engine jet, going through preflight procedures with one of the crews seated at the table. After roughly six minutes, the brief is concluded and the highly experienced pilots relax, some finding comfortable seats in the ready-room, others checking into crew quarters nearby.

“I think the hardest thing, though it doesn’t happen too often, is when you’re asleep and you’re called”, says Captain Lance Mussler. “You’ve got to launch in 30 minutes. You’ve got to wake up and have your wits about you. It’s important to be safe and you try to cover everything but there’s pressure to get airborne.”

Mussler, along with First Officer Gary Bernard and the other aircrew are on alert. But we’re not at a military air base. And the command center on the phone wasn’t the NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) Integrated Command Center at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs.

Hot-spare aircraft and crews are on alert to “protect” inbound and outbound “Next Day Air” volume.

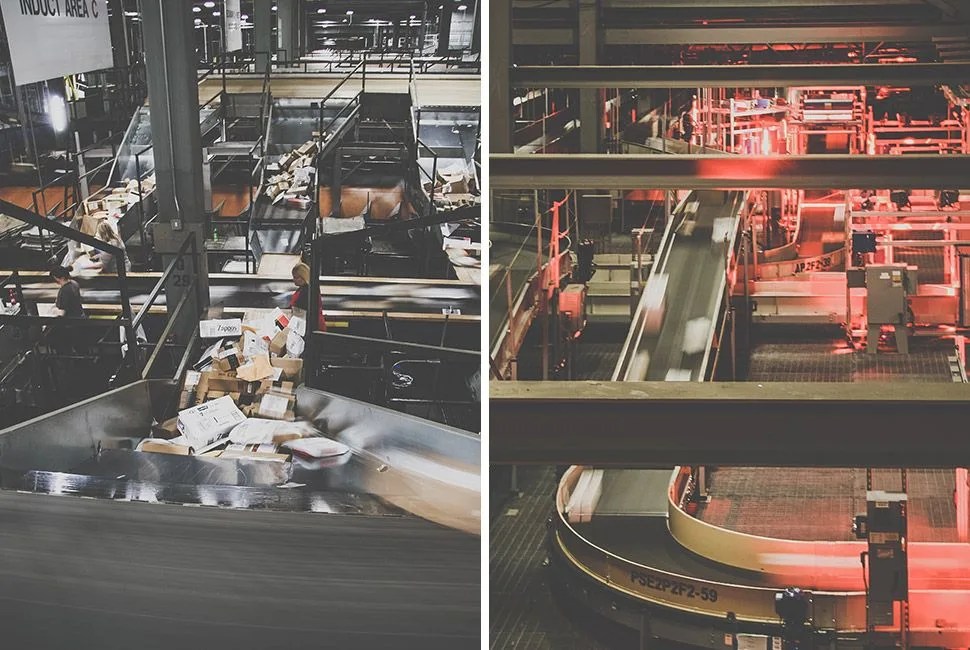

We’re in Louisville, Kentucky at the UPS Worldport, the largest fully automated package handling facility in the world and the main air hub for the shipping and logistics behemoth in the United States.