18 photos

Over the decades, the personalities of Formula One have changed — names like Senna, Mansell and Prost in the 1980s gave way to Schumacher, Hakkinen and Coulthard, and now Vettel, Raikkonen and Hamilton. Teams have faded along the way, and others have come to light. Technology has changed — the nuances of aerodynamics, tire wear, engine performance and braking have evolved. But one thing has remained: the ferocity of the Formula One race car. The spirit of wrangling that nearly unbridled power has stayed the centerpiece of this ne plus ultra racing series, and the machine — that low-slung rocket — has always been what makes F1 the fastest, most adrenaline-laced racing series on the planet.

MORE FIRST-HAND RACING: NASCAR Driving | Audi’s School of Racing | 24 Hours of LeMons

I, with a lifetime of fandom, have lived plagued by a question that first lodged itself in my brain 30 years ago. I sat, 14 years old, in my den with my Ferrari cap on, savoring the in-car camera views of a race, wanting to know one thing: What’s it like to drive that race car? I sensed how F1 contains a degree of magic in the man/machine partnership. I anticipated the feeling — those bulbous tires in my peripheral vision, the engine seemingly strapped to my back, the G-forces, the ground-level perspective — and I wanted to feel that energy in my own frame. I could watch the cars zip by, but what I really wanted was to grab that car and navigate it with my own two hands, my foot hard on the accelerator.

It’s basically a daylong car-porn fest, with the climax being the F1 drive.

Pirelli, the renowned tire manufacturer who provides nearly 40,000 of the carefully engineered rubber bits to Formula One every season (not no mention the other race series and millions of consumer vehicles), launched its Grand Prix Experience two years ago. Initially offering race enthusiasts the opportunity, to the tune of $1,000, to ride along in Pirelli’s three-seat F1 car, they upped the ante this year by introducing an actual drive event. For the first time, race fans can get behind the wheel of a Formula One car.

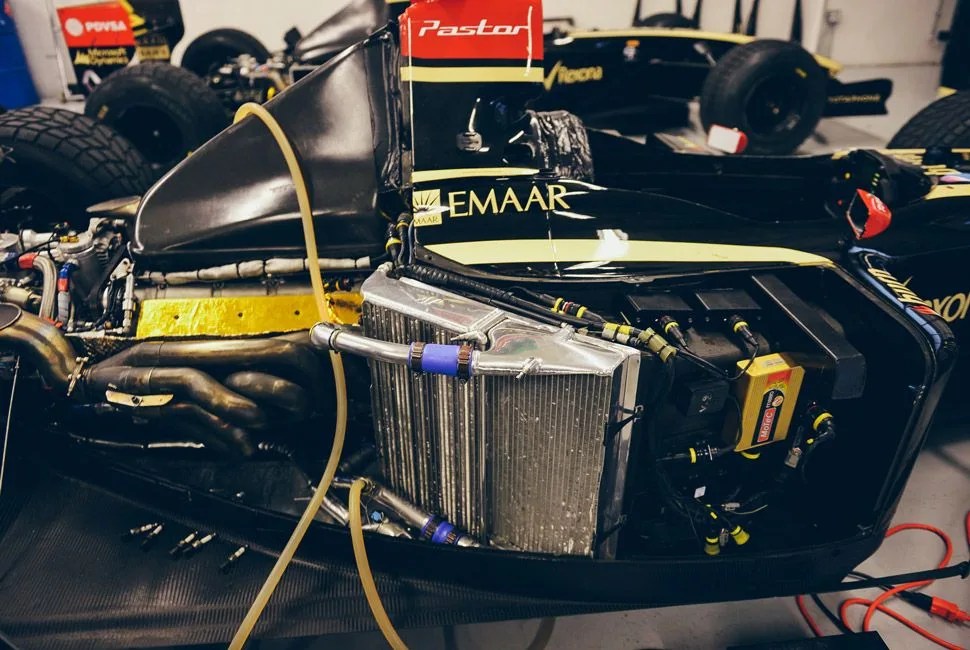

The vehicles aren’t quite current vintage — they’re former Renault and Benetton race cars with Cosworth, Judd or Peugeot V8 and V10 engines. They’ve been modified to help ensure safety and reliability, which is critical when your cars have to run all day long with a bunch of noobs at the wheel. But in terms of power, handling and overall geometry, they’re legit F1 cars, providing a comparable ride to current cars. “Many people share this dream”, says Jean Paul Libert, the visionary CEO behind the GP Experience. “So we set out to give our customers the opportunity to experience the impossible.”