8 photos

ROAD N✍TES

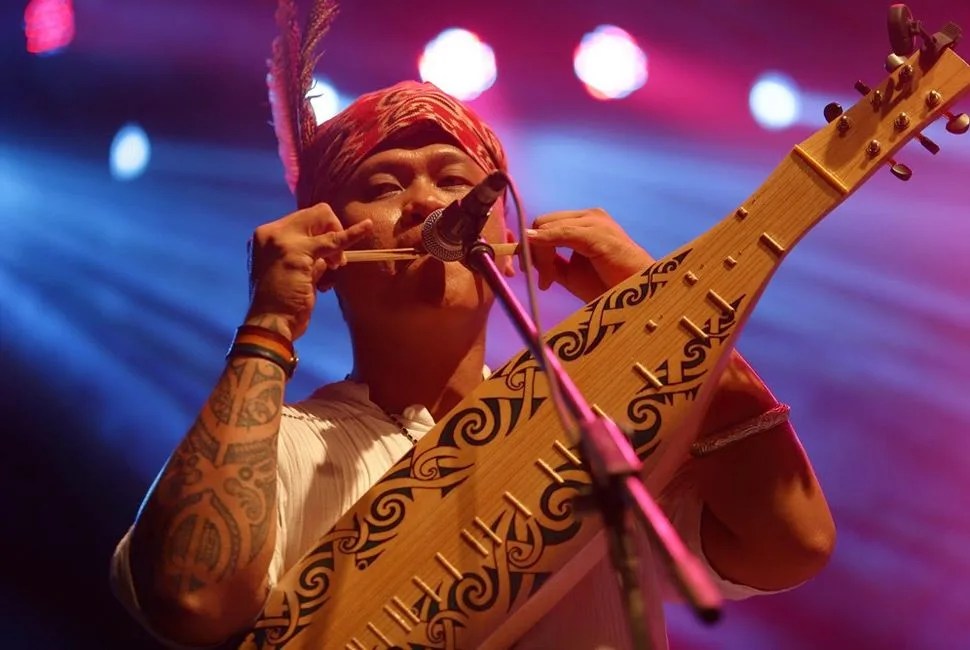

Editor’s Note: Where the South China Sea meets the rainforest in Malaysian Borneo, there’s a music festival unlike anything in the West. GP contributor Will McGough visited to dance, bang on drums and hear some of the best music of his life.

The coast turns the corner where the South China Sea is calm, the low tide more than tripling the size of the beach and revealing the smooth stones that dot the shore. The sun had come all the way up now, the sky changing from purple to light blue, and I could see the tree-covered saddle of Mount Santubong in the background towering over the stages of the Rainforest World Music Festival, set in the Sarawak Cultural Center on the forested coast of Malaysian Borneo.

MORE DISPATCHES FROM THE ROAD Dispatches from Cuba | A Key West Travel Guide | Running the Zion Traverse

Before, when it was still dark, I sat on the floor of an Iban longhouse, perched up in the canopy of the rainforest. The traditional dwellings of Borneo’s Iban tribe, longhouses resemble oversized tree houses that sit upon stilts in the jungle. The active ones still present throughout Borneo typically house over a dozen families, and a visit is like taking a trip into your grandfather’s toolshed, everything with a purpose and place. This particular longhouse, just steps from the two stages, was being used as a hostel during the annual three-day festival. It held a backstage atmosphere after the performances were done for the night, a place where the bands and backpackers — both from all around the world — gathered on bamboo mats.

I looked around the open-air room. There was a clean-cut guy from Spain, a fiddle player from a Canadian bluegrass band, a group of backpackers from Kuala Lumpur, the lead singer of a French a cappella group, and a few Irish gals who said the whole night had been “good craic.” Guitars, hand drums, tambourines, a didgeridoo, and beer cans. The French singer picked up one of the guitars, and a woman from Kuala Lumpur broke a piece of wood into two and began to bounce a beat off a two by four. The lyrics were all in French — which hardly anyone in the room spoke — but a few people, myself included, got up to dance anyway.

There was something about the sight of that no-name guitar player entertaining the crowd that clicked for me. This festival was not like anything I had experienced in the States, where crowds of groupies pine after some untouchable rockstar they feel they know so well. What makes it so unique is that, unlike most festivals and concerts across the globe, branded bands are not the draw. For the first time in my life, I went to a concert and did not sing along with a single song.